Everybody knows how to psych themselves up.

You visualize the outcome you want, or you remind yourself you have accomplished your goal before, or you find any number of ways to assure yourself you can do what you’re trying to do.

“The most evocative one for me is literally running down a line where thousands of people are giving me high fives,” says Alison Adcock, thinking of a motivational image once described by a research participant. “But I don't actually know that that was the one that worked the best.”

“People have reported it being a very powerful experience getting to be in the MRI, just seeing how something like a thought in their head can really cause this change in the feedback they’re getting.”

– Alison Adcock

Adcock, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, director of the Center for Cognitive Neuroscience and interim director of the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences, manages a lab that is working on using neurofeedback to help people improve outcomes on tasks. Rachel Wright, a grad student in Adcock’s lab, explains: “The overall goal is to help people learn how to increase their motivation while increasing activity in a region of the brain that we know to be involved in reward and motivation.” Some things people try work; some things don’t.

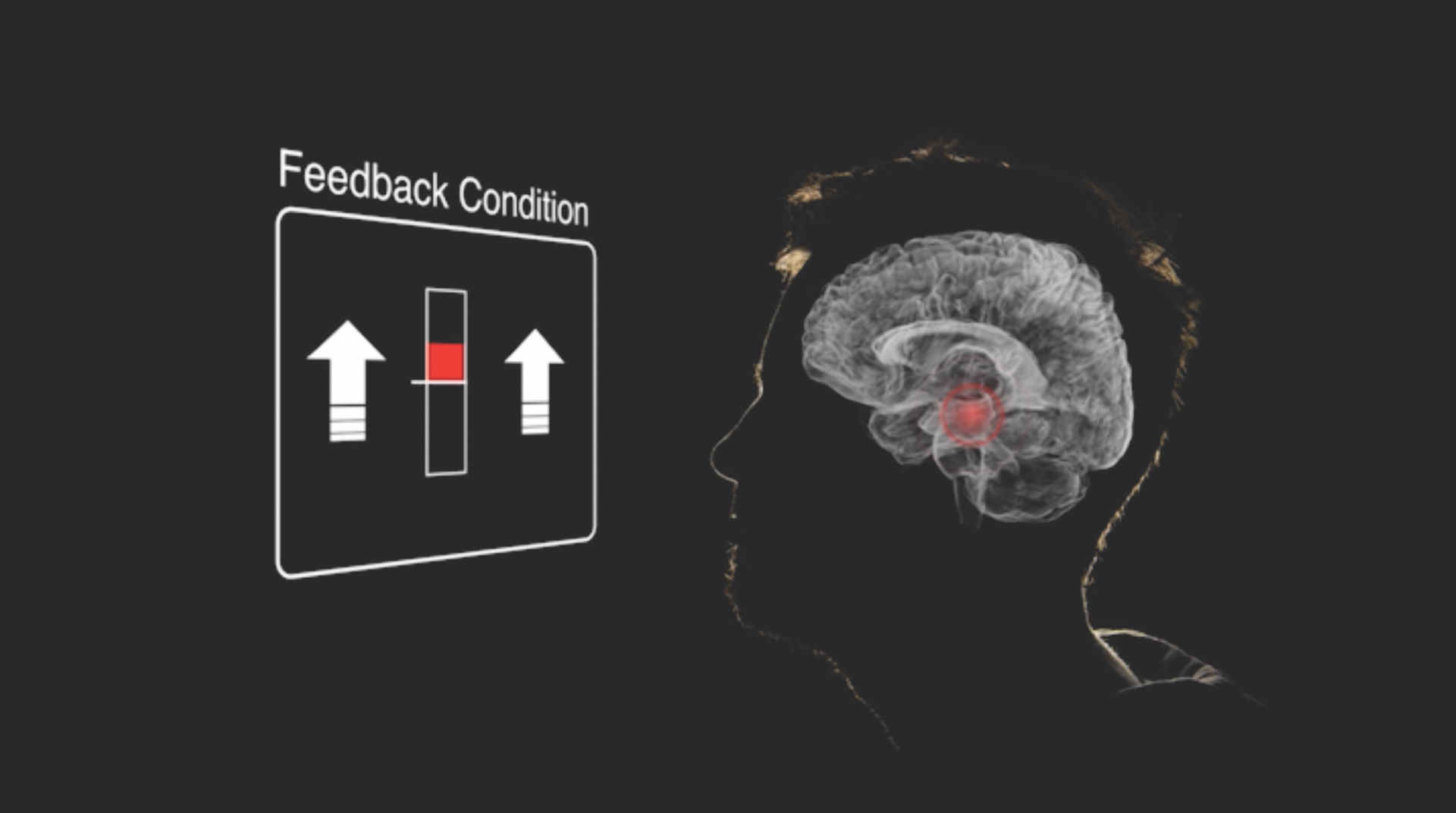

The lab uses magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) devices, which make high-resolution images of different parts of the body without requiring invasive procedures. Functional MRI (fMRI) tracks blood flow to different areas of an organ while the subject is inside the MRI machine. Thus Adcock and her lab partners put subjects in the machine and instruct them to think of rewarding or motivational experiences. A monitor shows the researchers whether the thoughts spark activity in known brain motivation centers, and they try to get the subjects to use their brains to improve that activity. “They have certain phrases they tend to go back to,” Wright says. “Music is a big one – mentally imagining the theme song from ‘Rocky.’”

Some thoughts may not work, Wright suggests, “because we’re not actually effectively recruiting regions of the brain that we know to be involved in dopamine and necessary for generating that kind of motivational state.”

When it works, Adcock says, “people that have participated tell us they refer to the experience.” Says Wright, “People have reported it being a very powerful experience getting to be in the MRI, just seeing how something like a thought in their head can really cause this change in the feedback they’re getting.”