Start with Scrooge McDuck, swimming in gold coins. That’s the first image you get when you hear that the Duke University endowment, having recovered from the collapse of the investment market during the beginning of the COVID pandemic, reached a high mark north of $12 billion. Twelve billion dollars, as a pile of wealth, is more wealth than entire countries have (Fiji is estimated to have about $9 billion; Liberia, $11 billion).

The market, and thus the endowment, has already come down from that high point, but still: It’s a lot. It’s the kind of money that would solve many world problems or, more locally, all of your problems — retirement, health care, college for your kids. With that kind of money, you could even afford to send them to Duke.

Speaking of college at Duke. You walk in from work and you check the mail; your spouse calls in from the other room. “Anything interesting?”

“The usual,” you say. “Bills, junk. Oh, also Duke wants some money again. Science, or scholarships, or the environment or something.”

“Again?” he cries. “Do they not know they have billions hanging around in their endowment? Tell them to skip coffee once a week. It's not hard to understand.”

We all get the letters, the emails, the calls from earnest undergraduates earning their work-study dollars. And then, likely, we sigh and send a check, big or little. But it feels odd responding to pleas for money from an enterprise sitting on billions of dollars. When the COVID crash caused Duke to freeze and even reduce salaries and spending, many suggested they just tide themselves over with a few wheelbarrows of cash from the endowment. Then the recovery meant that the endowment increased in fiscal 2021 by an astonishing 55.9 percent, leaping in a single year from $8.5 to $12.7 billion. But then, once more with feeling: “Hi, it’s us again; um, ….” It’s reasonable to ask: With all that endowment, when you need some money, why don’t you just go grab some?

Executive Vice President Daniel Ennis, who oversees Duke’s financial affairs, has heard the question before. And his first answer is simple.

“I can’t,” he says.

That is, in the first place, endowment gifts are specified as just that: gifts of principal capital whose earnings will support university missions. The capital itself can’t be touched according to agreements by which the money was donated. Moreover, the vast majority of gifts to the endowment come with restrictions. They’re for an endowed professorship, or financial aid, or the biological sciences — they’re for something specific. Duke almost never gets endowment gifts marked “mad money” or “just, like, if you need it or whatever.” People give gifts to the endowment because they want that money to work, in perpetuity, toward a specific end of their choosing, whether that’s helping first-generation students attend Duke or keeping the Divinity School divine.

Let’s parse that.

First, in perpetuity. Everybody gets frustrated with grandma, who at 87 is living like a pauper on only the earnings from her retirement plan. “Spend it down!” we cry. “You can’t take it with you — you’re not going to live forever!” That’s wise advice to grandma, but terrible advice to Duke. Duke can’t spend it down; unlike grandma, Duke does plan to be around forever, and it has to manage its endowment as if it will be. So that means it manages its endowment to earn at least a 4.5 percent annual return, according to Neal Triplett ’93, M.B.A.’99, president and CEO of DUMAC (once Duke Management Co.), the nonprofit support corporation for the university that manages the endowment. Again — like grandma — it spends only the earnings, and even then not all the earnings. Some of the earnings have to get plowed back into the endowment if you want it to grow. A return in the 4.5-5.5 percent range gives the endowment enough earnings to help run the university but also reinvest enough to keep the endowment growing. That’s the magic of compound interest: It’s only magic if you start getting interest on the interest.

As Ennis says, “We are in the elite talent business. Attracting that talent as a competitive matter is hugely correlated” with endowment capacities, whether endowed chairs for professors or endowed scholarships for students.

For example, consider that astonishing one-year growth of 55.9 percent in fiscal 2021. It sounds like that ought to be mad money — a few new buildings, raises for everybody, maybe new basketball uniforms. Except, first, that leap followed 2019, when the endowment grew by less than 7 percent, and 2020, when the COVID crash actually caused it to gain less than a percent. And this year’s market volatility has already diminished its value. Second, the earnings the endowment disburses to the university are averaged over a three-year period, specifically to smooth out those ups and downs. (And remember, that genuinely includes downs. In 2008 Duke’s endowment was $6.1 billion; it dropped almost overnight in the Great Recession and didn’t get back to $6 billion until 2013.) Much more important, by not treating that sudden leap as blue-sky money, Duke’s reinvestment of it ensures significant growth in annual working funds for the university’s missions. How significant?

“It’s on the order of $60 million of new money,” Ennis says. That’s $60 million more toward professorships, financial aid and other priorities. Every single year. “And that’s permanent money,” he says. “That’s sustained support of the missions. It’s a beautiful thing.”

So not just leaving the principal untouched but building the principal has long-term — perpetual — benefits that overwhelm any potential short-term benefit that might come from withdrawing capital. In fact, like a household borrowing money rather than using retirement capital when it’s time to buy a house, Duke will borrow money to address short-term needs rather than raid even such portions of the endowment earnings as it could.

Okay, that’s “in perpetuity.” Next, restrictions. All that capital has specific rules to where it goes. The endowment is really made up of around 5,600 individual endowment gifts, each given to Duke by someone with some idea of what Duke ought to do with it. Every university endowment has its own peculiarities: Stanford’s contains land they’re not allowed to touch; Dartmouth has an endowment focused on keeping wood in its president’s office fireplace. Duke’s most interesting complexity is the difference between the Duke University endowment and the Duke Endowment, which, confusingly, are two different things.

The Duke Endowment began with the famous $40 million James Buchanan Duke set aside in 1924 to create Duke University and support many other schools, hospitals, and charitable enterprises; it’s completely separate from the university. The gift the Duke Endowment gave to create and build Duke University that year was $6 million. Just accounting for inflation, $6 million in 1924 would be worth about $100 million today, and the $40 million of the original Duke Endowment, plus another $67 million he added when he died the next year, would be worth today about $1.8 billion. But the current Duke Endowment is worth $5.6 billion and has given away more than $4 billion in grants; the university endowment, after supporting the university since 1924, was worth $12.7 billion at the end of fiscal 2021. So clearly whoever’s been in charge for the last century has done a pretty good job. Further complicating matters is the fact that the endowments, though separate, are managed together, along with the endowment for Duke University Health System and a pension plan for non-exempt Duke staff, by DUMAC. The DUMAC board of directors includes Ennis, Duke President Vince Price, and a raft of high-level managers from the investment world.

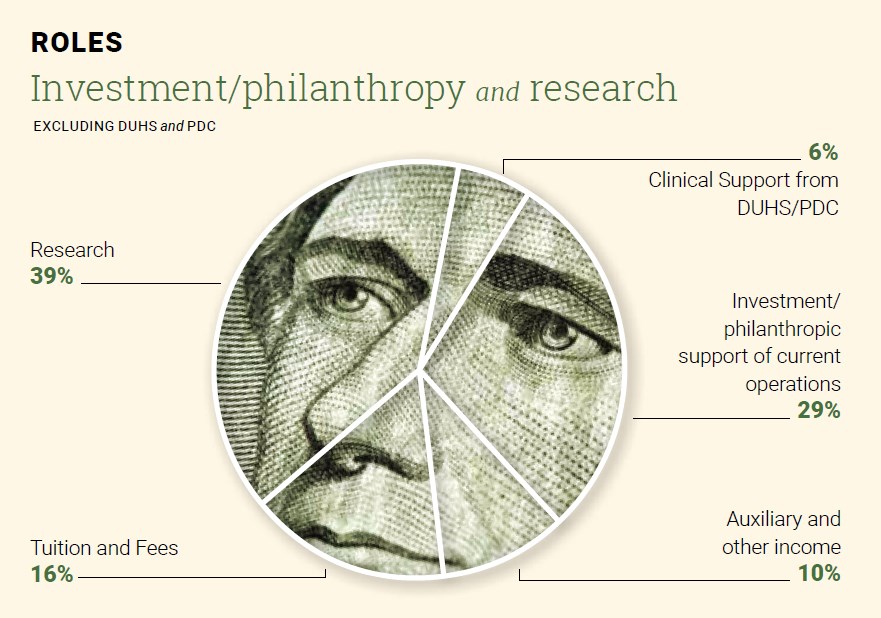

Now, as Triplett explained, DUMAC manages those various endowments so that they have a return of at least 4.5 percent or more. For the university endowment, that meant in fiscal 2021 around $643 million in payout, which constituted approximately 22 percent of the university’s $3 billion annual budget. That seems, oddly, both shockingly low and shockingly high. Low because really? That enormous endowment funds only 22 percent of the university’s annual budget? But high because … that’s north of $600 million dollars, which is a lot any way you look at it.

And again, that’s every single year. The university budget gets another 7 percent from annual giving and other philanthropy; 16 percent from tuition and fees; 39 percent from research funding (from government and other sources) and 16 percent from various other sources.

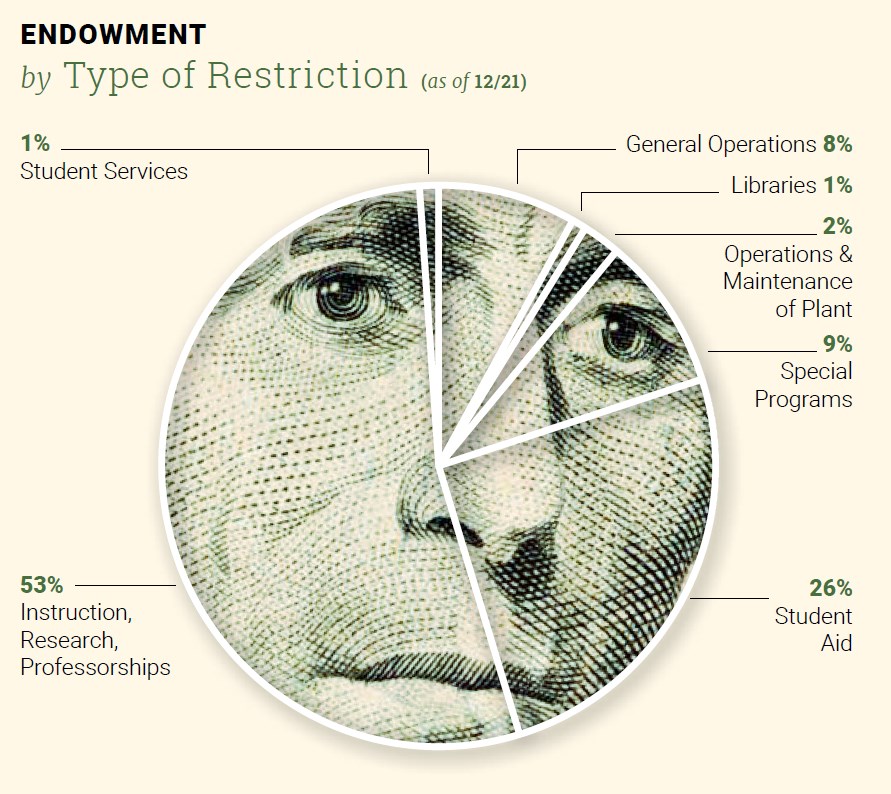

And what that 22 percent from the endowment funds, as Ennis noted, is highly structured. The 5,600 separate individual endowments are contractually dedicated to something: financial aid; students of a particular subject; students of a particular background; research into a particular topic. The university can’t change that. An endowment goes on in perpetuity, and so do the rules for its earnings. Only about 29 percent is not strictly dedicated.

More than half of the limited principal, $6 billion (or 53 percent of the $11.3 billion in limited endowment funds), goes to research and instructional goals, including endowed professorships. And if you’re wondering, if you hit the lottery and want to keep a professor busy, “Three and a half million,” says provost Sally Kornbluth. That’s what it costs a donor to fully endow a professor. “That spins off money that supports either that faculty salary or their research.” A smaller investment will endow an associate or even an assistant professorship. Sometimes an endowment follows a professor; sometimes professors move from one endowed position to another.

As Ennis says, “We are in the elite talent business. Attracting that talent as a competitive matter is hugely correlated” with endowment capacities, whether endowed chairs for professors or endowed scholarships for students.

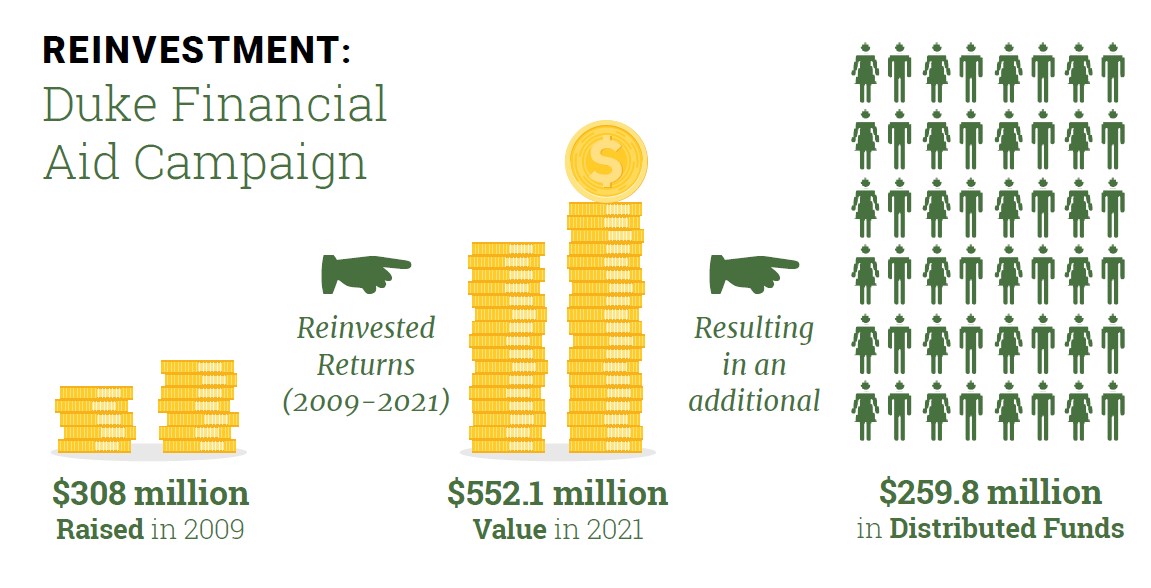

Another quarter of the limited principal funds student aid, though even that $2.8 billion is nothing like enough to allow Duke to provide loan-free aid to every student who needs it. Princeton, for example, makes that commitment. Princeton’s endowment is $37.7 billion, which apart from being nearly three times Duke’s, was in 2020 approximately $3.4 million per full-time-equivalent student. By that measure Duke’s in 2020 was about $534,000. In 2009, after a four-year campaign, Duke added $308 million to its financial aid endowment, but Vice President for Alumni Engagement and Development Dave Kennedy estimates Duke would need at least another billion dollars to make a commitment like Princeton has. Would a number like that finally let reluctant alumni philanthropists off the hook? “It would be a nice problem to have,” Kennedy says, but then echoes one of two points both Ennis and Kornbluth make: Even if financial aid is fully funded, Duke will always need to fund some other university priority — some research, some program, some pursuit. Duke will never stop needing philanthropic support. More important, compared with its rival schools, Kornbluth notes, Duke is underendowed.

Wait, what? Yes, a school with a $12.7 billion endowment can be considered underendowed, if you compare it to places like MIT ($27.5 billion) and Harvard ($51.9 billion) and the University of Texas system ($42.9 billion). Those are the peers with whom Duke competes for professors, for students, for grants. As Ennis says, “We are in the elite talent business. Attracting that talent as a competitive matter is hugely correlated” with endowment capacities, whether endowed chairs for professors or endowed scholarships for students or endowments that fund research enabling professors to spend less time chasing the grants that constitute 39 percent of Duke’s annual operating revenues.

As for keeping Duke competitive by keeping the endowment growing, Kennedy is hopeful for the future. He says as a comparatively young university, Duke has what he characterizes as missing older alumni. The beginning of Duke’s rise to prominence came in the 1970s, so “most of our core donors are basically about a decade younger than most schools’ core donors.” Given that people amass wealth as they age, he’s hopeful that as Duke’s core donors age into their core giving years Duke’s endowment will continue to grow. Many large donors include an institution in their estate planning, and estate gifts are more likely to be unrestricted, which is a sort of holy grail of endowment funds: It means the money they generate can be used for anything the university needs.

Which is key. Within those unrestricted funds, university planners make decisions every year about priorities: the sciences, the climate, healthcare. Responding to needs and desires, Duke never runs out of new goals and pursuits. More, unrestricted endowment funds often support other philanthropic gifts that, while enormously generous, contain hidden costs. Think of a building. If you win the lottery again and want your name on a building at Duke, it’s going to cost you at the very least $20 million, though likely more, depending on the building. But say you generously pay for the entire building. Everybody smiles, and they cut the ribbon. And then, with your gift consumed, Duke needs to heat and cool that building, to furnish and equip it, to maintain it, and to fill it full of professors, researchers, and students. Every year.

Which is where that notion of unrestricted endowment funds is something of a holy grail. Vice President for Finance Rachel Satterfield cites the example of Washington University, one of the few peer schools whose endowment recovered even more strongly than Duke’s. They put that billion dollars into their financial aid endowment, which led people to suggest to Satterfield, “Seems like in a good year, you should be able to just solve all the magic problems you have.” She explained to them all the complexities about an endowment, with the simple addendum: “I think the difference was [Washington University] had a lot more unrestricted resources in there than we did.”

Which is something of a goal. “I would love for you to give me money and say, ‘I would like to entrust you to do whatever you think is the next most important thing to do.’” Which answers the question: What do you give the university that has, if not everything, then $12 billion towards everything? You give them choice, and the capacity to respond. When does it stop? Probably never; recent market volatility may mean that by the time you read this the big gain may be a distant memory. Or maybe it stops when the next most important thing to do is to swim in the endowment like Scrooge McDuck.