Balu Sesay had been blind for 29 years when Lloyd Williams first met her. It was a sweltering day in July 2021, in a small hospital exam room in Freetown, the bustling port capital of Sierra Leone. The Duke eye surgeon saw immediately that both of Sesay’s eyes were badly damaged, the right one completely ruined and a milky haze covering the left, both the result of injuries she sustained as a teenager. Now 46 and the mother of five, Sesay had never seen her husband or her children.

What brought her to Freetown, nearly three hours from her home, was a promise she still couldn’t quite believe: that her left eye could be fixed, that her years in the dark might end.

The next day, Williams worked with a team of Sierra Leonean ophthalmologists to replace the opaque cornea in her left eye with one from a donor. It was one of eight corneal transplants that week, the first ever performed in the West African country. Twenty-four hours later, when doctors removed the patch protecting her repaired eye, she walked into the waiting room and toward a teenage child whose eyes were flooding with tears. “Girl, why are you crying?” she asked in Krio, the local language.

“Mom, it’s me,” the girl cried, reaching out to embrace her mother. “I am your daughter.”

Even for Williams, who has performed hundreds of vision-restoring surgeries in the United States and other countries, those moments are soul-stirring. It’s why he’s back in Freetown nine months later, having traveled 7,000 miles, taking three planes and a boat, clutching a Styrofoam cooler packed with human eyeballs.

“It’s the closest we can come to performing miracles on Earth,” he says.

“Miracle” is a word that Williams, a devout Christian and the son of Lutheran missionaries, invokes with a good deal of reverence. He notes that healing the blind is among the most frequently described miracles attributed to Jesus. But as a scientist, he knows what he and others are doing to restore sight in places like Sierra Leone is not divine intervention. It’s actually pretty straightforward ophthalmology.

Consider that cataracts — the most common cause of blindness globally, leaving more than 17 million people with no functional vision — can usually be fixed with a simple, one-time surgery that costs as little as $12 to perform. Millions more, like Balu Sesay, could have their vision restored with a corneal transplant. In fact, according to the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness, more than three-quarters of the estimated 43 million people around the world who are blind could regain sight through medical intervention.

That so many remain in darkness is primarily a function of the massive inequities in global health care. Ninety percent of people with preventable blindness live in low-income countries, which often lack the resources to offer anything like comprehensive eye care. In sub-Saharan Africa, there are just 2.5 trained eye specialists for every million people, akin to a city the size of Durham having only one eye doctor. Problems like cataracts or glaucoma, which are typically painless and progress slowly, often go untreated for years, eroding vision until a person is left completely blind.

"There are no campaigns in West Africa to tell people to go get their eyes checked,” says Leon Herndon, a Duke glaucoma specialist who has done clinical research and training in Ghana and Nigeria. “There’s very little education about eye diseases, and many people believe that once you lose vision, it’s just hopeless.”

And that makes restoring vision — and with it, hope — a powerfully addictive feat. Williams first felt its pull as a medical student at Tufts University, when he spent a summer break in 2001 volunteering at a hospital in the remote high plains of Zambia, in south central Africa. One day, an American doctor asked him to check on a blind woman who had undergone cataract surgery the previous day. Williams and the doctor removed a patch covering her eye and huddled over her bed, asking what she could see. “White people,” she responded in a local dialect.

“I thought, this is the most amazing thing I’ve ever seen,” Williams says. “For the most part [in medicine], you don’t get many wins. You’re just managing something. But, I thought, I could do this for the rest of my life and never wonder whether what I did was worthwhile.”

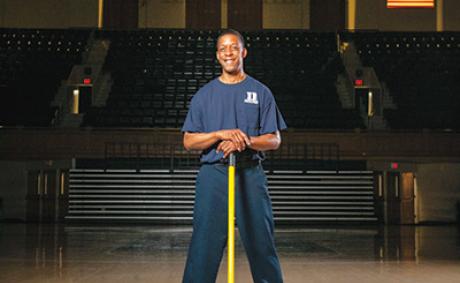

After finishing medical school and joining a private practice in Utah, Williams threw himself into that mission with characteristic, high-motor zeal. A competitive cyclist who builds guitars to unwind, he crammed his calendar with trips abroad, usually funded by himself or with small donations. He estimates he has done some 700 cataract surgeries in countries including Nepal, Guatemala and South Sudan. His most recent trip to Sierra Leone was his 16th to Africa since unbandaging his first patient in Zambia.

But such drop-in visits are a Band-Aid solution at best. Williams came to Duke in 2019 to work on something more sustainable. He now leads Duke’s Global Ophthalmology Program, adroitly rebranded as Duke GO, which is aiming to provide more structure to the international efforts of several Duke eye doctors across Africa, Asia, and Central America. The point is not just to help eye doctors in those places, but to empower them, he notes.

“No one person is going to end preventable blindness alone,” he says. “We need an army of people.”

In Sierra Leone, that army’s field general is Jalika Mustapha, a dynamic young ophthalmologist who leads the country’s national eye program. A native Sierra Leonean, Mustapha graduated from medical school in Kenya in 2016 with the highest board scores in all of Africa, and she has won international praise for expanding access to cataract surgery and preventive eye care in the country’s rural interior.

Since Mustapha’s team is already doing cataract surgeries, Williams is focusing on teaching more advanced procedures such as corneal transplants, which have only been done in a handful of places in Africa. Mustapha has now taken the scalpel for three transplants, becoming the first Sierra Leonean doctor to perform an organ transplant in her country.

That first earned Mustapha and Williams a spot on the national news and a meeting with the health minister, a big deal in a country still battling COVID-19 and other public health crises. With annual per capita spending on health care at just $46 — about 1 percent of what wealthy countries spend — eye care doesn’t often get such attention on the national agenda. But when the minister asked Mustapha to dream big, she didn’t miss a beat.

“We need a new eye center,” she said. “We need to be able to do more surgeries, and we need a place to train more people in our country.”

She came away with a promise of land to build the country’s first dedicated eye hospital. Williams hopes it will eventually be a site where Duke ophthalmology fellows can train. “Sierra Leone, I think, is at a tipping point,” he says. “The doctors there are very good, and with just a little bit more money and support, they have an opportunity to make a massive difference, not just for their country, but for all of West Africa.”

Of course, a tipping point can still be a precarious place to stand, especially when you’re holding a scalpel.

While she works toward construction of a new eye center, Mustapha runs Sierra Leone’s national eye program from two small rooms in Connaught Hospital, which occupies a gated complex just off the Atlantic Ocean in central Freetown. On his April 2022 trip, Williams has ferried 20 donated corneas from North Carolina, and all week, patients and families filter into a bright waiting room near the entrance, their anxious banter mixing with the sounds of trucks and motorcycles whizzing by on the city’s busy streets.

On one afternoon, the doctors are in the middle of surgery when the power goes out. Nurses grab their mobile phones, ready to shine light so the doctors can complete the procedure. The hospital’s backup generator kicks in within a minute, but it’s a reminder that medicine in a developing country can test one’s resourcefulness.

In Sierra Leone, for instance, there’s no general anesthesia for eye surgeries, only a local numbing shot, and so doctors must anticipate a patient twitching or squirming. When it’s time to make the delicate sutures to knit the donor cornea in place, everyone holds their breath. One patient, overcome by nerves, stands up right before the first cut and leaves. She returns a few days later and this time makes it through the procedure.

“It’s really remarkable what the doctors are able to do with the resources they have,” Williams says.

But any obstacles the doctors face pale compared to what their patients have overcome. Most African countries have virtually no accessibility services or legal protections for the disabled, making it significantly more difficult for people who are blind to support themselves and live independently. Many who lose their sight find they can no longer work or even navigate to do simple errands. Children or grandchildren may be held out of school to care for blind elders, perpetuating a cycle of poverty that can cripple a family for generations. In places like Sierra Leone, where most people support themselves through manual labor and farming, a blind person is sometimes described as “a mouth with no hands.”

For Williams, understanding the shame and scorn steeped into such labels makes those moments when the bandages come off all the more profound. He reflects for a moment on the notion that he is giving someone their life back, through his surgery. “Honestly, in Africa, I think you are. When you think about the social and spiritual effects of believing you are worthless, believing you are a drain on your family … I think it is giving them their life back.”

You can sense the nervous anticipation as patients and families wait for pre- and post-operative appointments. On the days following surgery, when they first realize they can see, everyone cries with a mix of joy and relief, thanking God and the doctors in equal measure.

But the sense of rebirth is never more palpable than when the people who received transplants during the first round of surgeries in 2021 return for follow-up appointments. Balu Sesay, the mother of five, has a job as a housekeeper, and she brags that she now can see when her children aren’t doing their chores. Another woman whose deteriorating vision nearly caused her to lose her position in the military shows up in combat fatigues, her career back on track.

One day, a 20-year-old woman strides into the exam room wearing a bright red top and a broad smile. There had been no smile when Williams first saw her nine months earlier. She had been blind in both eyes for 10 years and described herself as “hopeless” and “just crying over and over about my sight.” When Williams asked her what she wanted to do with her life, she stared blankly at the floor and mumbled, “Nothing.”

Now, with a clear cornea in her left eye, she brims with newfound purpose. “It was not easy to lose [my] sight,” she says in a video interview after her follow-up appointment. “Before, someone walked with me, while now I am walking for myself. I can do everything for myself. I can read. I can write. I can even cross the streets. Before I was not doing any of this.” She tells the doctors she now aspires to be a politician.

A few weeks later, Williams is back in his Duke Health clinic, reminiscing about the trip. He watches the video again and smiles. “That’s a win,” he says. “That’s as big a win as you can get.” Because it’s not just that she’s regained her ability to see the world. It’s that now she can see herself in it.