Before she left home for her freshman year at Duke, Jenn Yang ’07, M.B.A.’14 cleaned out her room. One thing she kept was a box of handwritten letters from throughout her childhood. “I stored those letters in a box in my closet and largely forgot about them,” she says.

Then, visiting her folks in 2021 during the pandemic, she rediscovered them. “The handwriting, the torn edges of the envelopes, and the little trinkets inside were as precious in my grown hands as they were when the letters first arrived in the mailbox years ago,” she says. One that especially tugged at her was an unsent letter to a third-grade friend who had moved away. Yang found the emotions her third-grade self had poured out still in the box, unsent, because her parents had briefly run out of stamps.

An unsent letter, a box of memories, a missing stamp. “That gave me the idea that I could probably make some kind of kit or product to help kids have all the things they need to write a letter.”

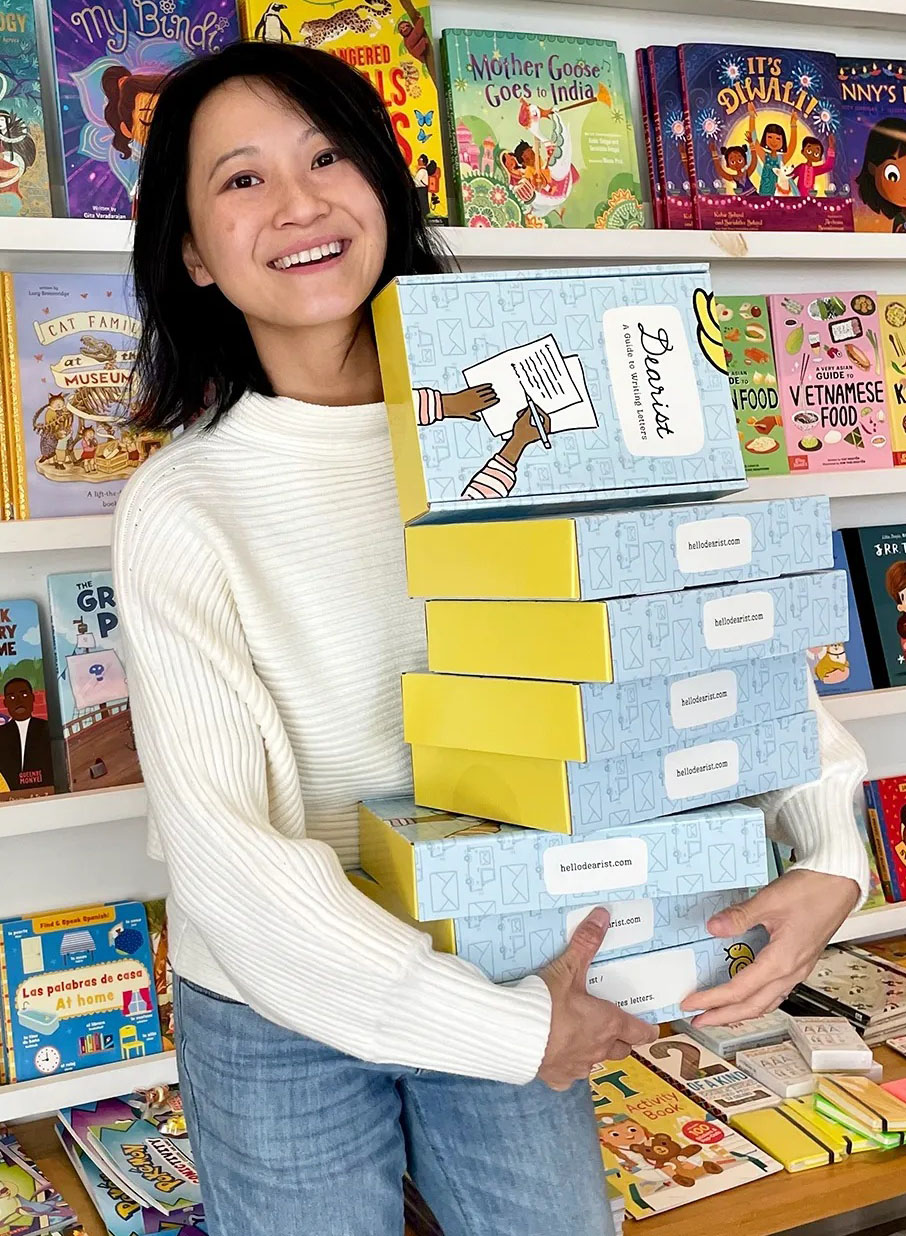

Meet Dearist, a small cardboard box containing several little books about how and why to write letters, along with three slim packets, each containing paper, envelopes – and stamps. And it’s about more than just making it easy for kids to write letters. The Dearist kit also provides instruction on what a letter is and answers the questions “Why would you write a letter?” and “What is the mail?” Her own kids ask those questions.

Commonly, since the teaching of cursive is no longer certain in many schools, kids don’t even learn how to address an envelope. When Yang took her first steps in developing Dearist, giving stationery and stamps to kids of friends and family and offering an idea and saying, “Let’s write a letter about this,” she recalls, “a lot of the kids just did not know what I was talking about.”

The road to Dearist wasn’t quick or simple. Yang had wanted to start a business, but “this is completely out of the realm of what I thought was possible. For a long time I never thought I could find a way to combine my love of writing and reading with a business venture.”

She sells the kits on her website, hellodearist.com, and she’s had some interest from bookstores and such. But where Dearist has begun to take off is in classrooms. Yang has had supporters pay to put Dearist boxes in schools, where teachers have used them to encourage writing and pen-pal relationships, and Yang points out that research regularly shows that writing by hand uses areas of the brain that typing does not develop.

Over years of design and tryouts and explaining to kids what stamps were and why we use them, she developed Dearist into its current form, including those little books that explain how the postal service works, what a stamp is (and how to design one), the parts of a letter, how to address an envelope, and so forth. That’s important, says Christine Geier, a second-grade teacher in the Vieja Valley Elementary School in California, who organized a pen-pal connection with another school an hour away.

“They had no idea,” she says of the kids addressing their first envelopes. “And just even to write that small, to get the letters on the envelope.” Geier, too, talked about studies showing the value to brain development of writing by hand, but she said the greatest benefit from the program was joy: “The joy and excitement of the kids, getting to write their letters and add little pictures and doodles and fun, fun things.” She said the kids’ anticipating replies from their pen pals “was just like Christmas or their birthday, they were so excited.” At the end of the school year, the two classes met and the pen-pals got off buses – “they just zoomed, attached to each other.”

Yang sees Dearist, ultimately, as a kind of anti-AI, a counterpunch to our increasingly virtual world: an actual physical-reality interaction. It creates artifacts, using senses, not just keyboards, and she’s hoping to get it into more schools and work with more teachers.

“It’s a literal paper trail of the past,” she says. “And that’s something that you don’t come across very often these days.”