It can be difficult for a student in 2023 to imagine the world of Duke students 50 years ago – a world without smartphones.

However, The University Experience, a student publication that ran from 1968 to 1978, offers us one glimpse into the quickly changing experience of Duke students in that decade. Published by the Duke chapter of the YM-YWCA (formerly two groups, the Young Men’s Christian Association and the Young Women’s Christian Association), the book was intended for incoming freshmen, as the Y was closely involved in orientation. The Y was an emphatically activist student organization and had particular interests and concerns with social movements on campus and nationally: the anti-war movement and the draft; issues of racism, particularly that experienced by Black students and staff; and women’s rights and feminism.

“This year’s Black freshmen will know what it is to be important.”

- HARV LINDER ’72

Before 1968, the YMCA published the perhaps stodgily named Duke Gentleman, and the first issue of The University Experience, also published by the YMCA, followed that model: Hearty welcomes from the mayor and Duke’s president, an overview of campus history, and even a description of the university’s capital campaign filled the book. Rules and regulations, such as the judicial code and the constitution of the student government, were printed in full. However, an essay titled “The University Experience” by Peter Hobbes alludes to the increasing unrest on campus. “It is increasingly difficult to ignore the forces of social change that are at work at Duke and in the nation as a whole.”

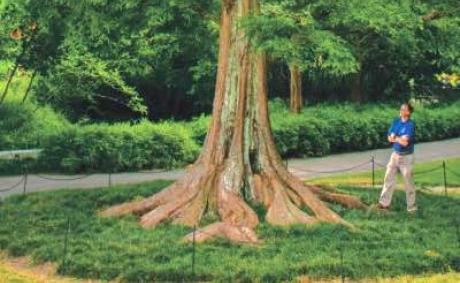

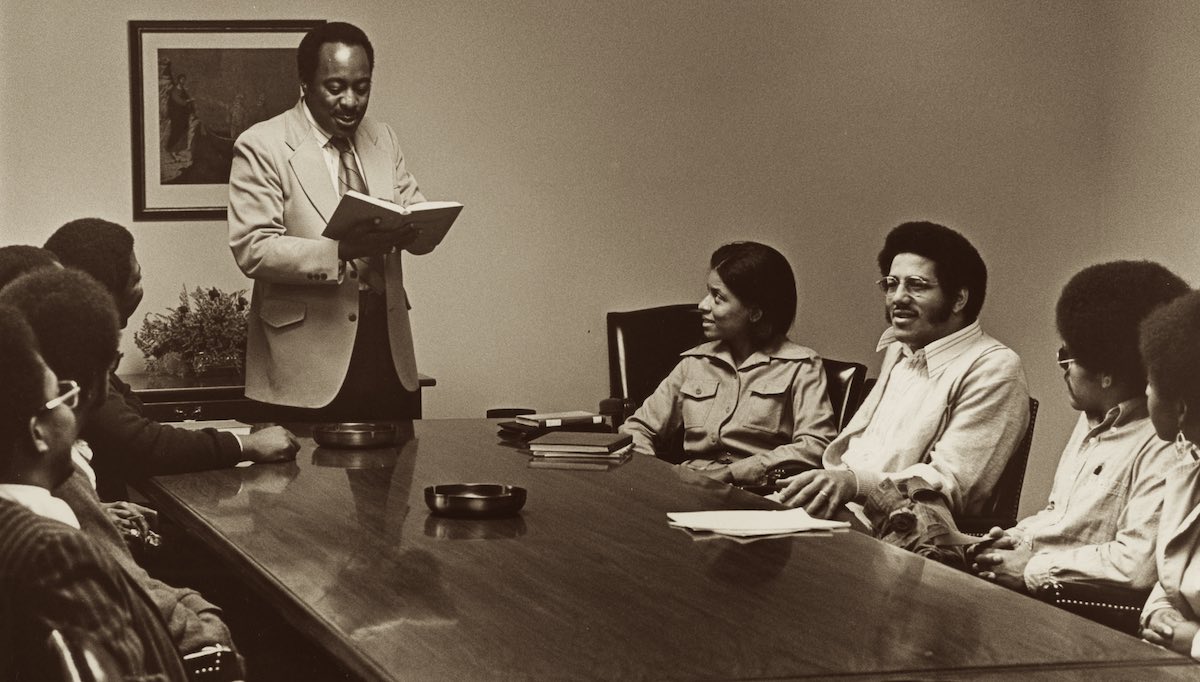

The 1969 version of The University Experience was the first to be published by the merged YM-YWCA. Fresh off the heels of the Feb. 13, 1969, Allen Building Takeover, a Black student protest in which police fired tear gas on hundreds of students who had gathered around the building, it strikes a different tone. The Editor’s Introduction notes wryly that “The University Community is changing so rapidly that some of what is included in this handbook at printing may be obsolete when you arrive at Duke.” While the publication still contained overviews of student groups, residential life and Duke traditions, considerable space was devoted to racial issues at Duke. The YM-YWCA consisted largely of white students, and for the first time, a specifically Black perspective was added. Student Harv Linder ’72 addressed the incoming Black students: “Black students at Duke are not sitting back waiting. We are moving forward, and we invite you as freshmen to join us. This year’s Black freshmen will know what it is to be important. You will discover that you are not only an asset to the university in that you will broaden and enrich that which has been termed ‘the university experience,’ but that you will be one of the most important assets that the Black students already at Duke will have. Your class will double the number of Black students at Duke.”

By the Book: Covers from The University Experience, from left, 1971-72, 1972-73, 1975-76, 1976-77.

The 1970 University Experience was distributed directly to freshmen in the fall, not mailed over the summer as it had been in previous years. A slip inside offered a disclaimer: “This booklet is published to acquaint you with a student perspective of some of the situations that you will encounter at Duke. It is published by the YM-YWCA and as such is not an official University publication.”

After receiving a copy, Duke Chaplain Howard Wilkinson wrote a memo to the publication’s staff. The majority of his memo appears under the subtitle “The Bad Things.” These included articles he felt were unfairly critical, the use of expletives, and its “general mood of negativism.” He concludes, “There is one good thing about all the whining, bitching, whimpering, complaining, distortion and slandering in the booklet. If a freshman gets to Duke in spite of the booklet, and if he should discover anything good at all – in addition to the “Y”– he will not only be shocked, but he may even find in this glimmer of hope that perhaps something else here is not as almighty rotten as this booklet led him to think it would be.”

Despite the reproachment, the editors of The University Experience continued to highlight the concerns and pressures students felt. Sections on the use of narcotics, opposite sex cohabitation, and the women’s movement at Duke presented a frank look at what editors thought incoming freshmen would want to know. In 1973, for the first time, space was devoted to gay students, called “Being Gay and Proud.” Written by members of the recently formed Gay Alliance, the section explained their purpose. “For those of you who are gay we provide a community in which you can meet with other gay people, not pick-ups. For those with questions or problems we provide confidential counseling and referral. For the straight community we provide educational material and speakers (as well as our own openness) to foster the growth of an empathetic society, one in which both straight and gay can function and produce without being enslaved for sexual adaptation.”

As the 1970s went on, the publication shifted again. The Vietnam War now over, the Y remained focused on racism and sexism, and The University Experience expanded to include issues such as prison reform and environmental justice, until ceasing publication in 1978. The handbooks now serve as rich documentation of student life, and we are grateful to be able to steward and preserve them.