When he was a boy, groundbreaking neuro-oncologist Darell Bigner M.D.’65, Ph.D.’72 watched things grow.

Raised on a small farm in Mississippi in the 1940s, Bigner nurtured tomatoes his dad made him plant and tend in exchange for spending money. His family had cows and Bigner grew up alongside them, dreaming of becoming a veterinarian.

In college, his interest shifted to human medicine. Starting his medical education in Georgia, he transferred to Duke in 1963 – and has stayed here almost continuously since, except for his military time doing neurological research from 1968 to 1970 at the National Institutes of Health.

Bigner came to Duke because he was interested in a different kind of growth: brain tumors. Duke was well known for its brain tumor work, even if it was rudimentary by modern standards.

“Back then, the word ‘neuro-oncology’ hadn’t been invented yet,” Bigner says in his relaxed Southern drawl. “When they would open the dura,” – the membrane between the skull and the brain – “they would actually have to take their finger and feel around to feel where the tumor was.”

Mentored by field pioneers Drs. Barnes Woodhall and Guy Odom, Bigner grew to love the interplay between the research and the clinic, the doctors and the patients. He took advantage of the unique emphasis of Duke’s medical education program in research, which he continued after getting his M.D. in 1965.

As if working on a Ph.D. while being a neurosurgery resident wasn’t enough, Bigner was drafted into the Navy during the Vietnam War. He was told his surgical expertise would land him 300 yards behind the frontline Marines in a tent hospital.

“I went in to see Dr. Woodhall and he said: ‘Son, I think you might get killed like that,’” Bigner recalls. “He picked up the phone and got me transferred out of the Navy and into the Public Health Service.”

Going up to the National Institutes of Health for a couple years was about as far north as Bigner ventured professionally. Years later, when prestigious northern universities tried recruiting him, he balked after a cold-weather visit.

“The worst thing to do with a Southern boy is try to recruit him in February,” Bigner chuckles.

Back at Duke, the brain tumor work continued to heat up. As more and more patients came, they also became more integrated into the process – even helping raise money through an annual 5K run and walk for research.

“I don’t know of another program that has the patients that are as involved in that manner as we do,” Bigner says. “They’re the thing that drives us.”

“Us” includes a tight-knit clinical and research group at the Preston Robert Tisch Brain Tumor Center, where Bigner is founding director along with deputy directors Drs. Henry and Allan Friedman.

“He has a generous but tough brand of science that makes you focus, which was really beneficial in my career,” says Dr. David Ashley HS’95, who came from Australia specifically to work under Bigner in the 1990s and then returned at Bigner’s invitation to take over as director of the center. “I had lost my father – he died of a very nasty cancer when I was in my early twenties – so Darell became a surrogate parent figure for me on the other side of the world.”

Wanting to provide the best care possible for patients, Bigner has spent decades parsing the genetic and molecular machinery of brain tumors, leading to a new understanding of the genetic drivers of cancer.

Most recently, his identification, with Drs. Bert Vogelstein of Johns Hopkins

and Hai Yan of Duke, of how mutations of the gene IDH are linked to particular

tumors – seminal work that was published in 2009 – became the basis for Voranigo, the first drug in decades for this patient population. It was approved by the FDA in mid-2024, showing the difficult road to developing new treatments.

“It takes so long,” Bigner says. “But I think all our patients know that we’ve offered them the very best that there is. We never give up.”

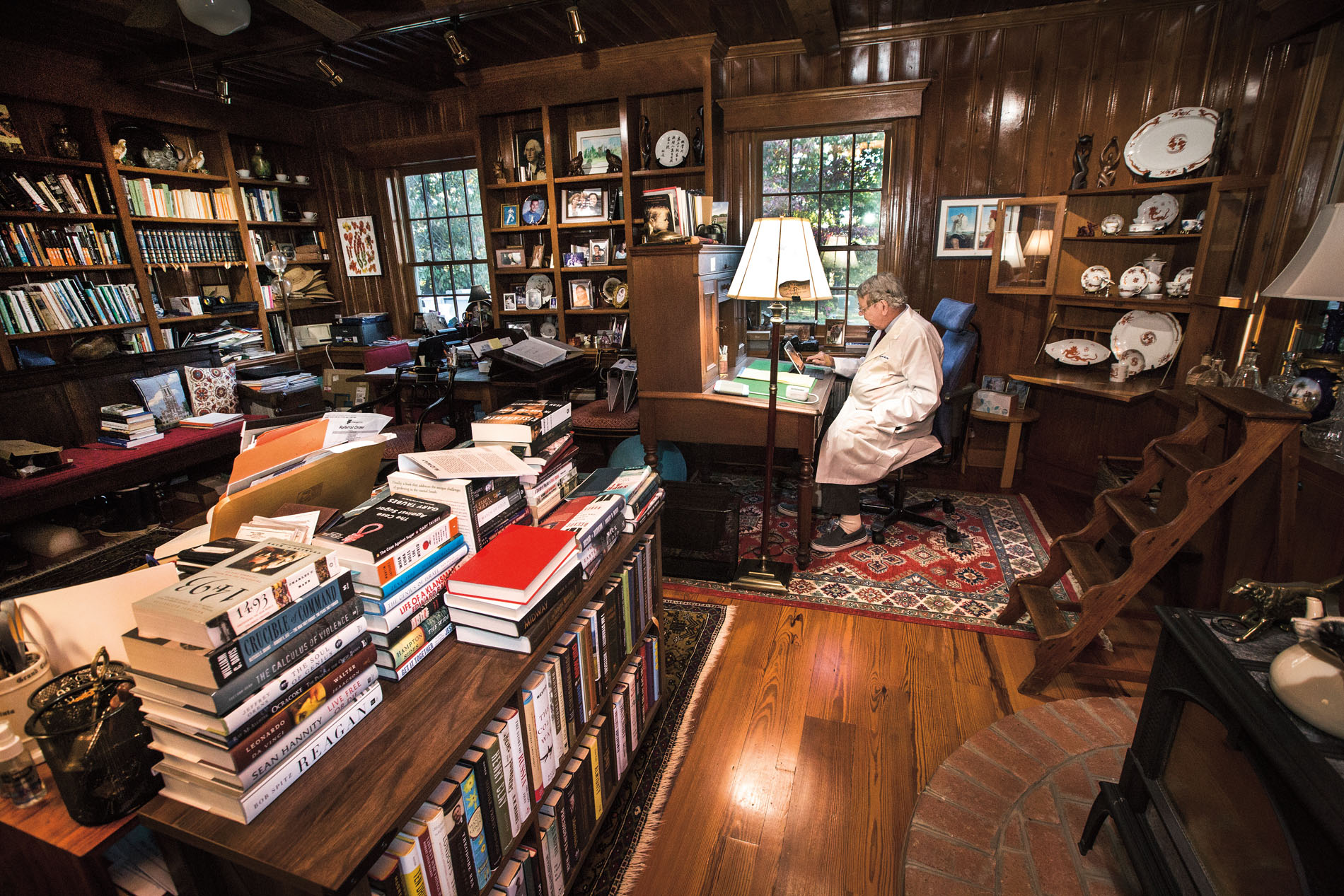

Bigner is still conducting research, with two FDA investigational drug permits that he estimates will take five years of clinical trials to complete.

It’s all coming full circle as well: He lives on a farm again, where he and his wife, Rita, grow hay, chestnuts, and – yes – tomatoes.

“I’ll give you some next year, if you like,” Bigner says, as he leaves to tend the garden of clinical research.