Susan Cook ’88 did not come to Duke expecting to stir things up. “I didn’t really think of Duke as a protest school,” says Cook, who nonetheless made a profound contribution to the spirit of protest that has ebbed and flowed at Duke throughout its first century.

In 1986, Cook told the Duke community something most of the community did not know – that the beautiful campus of Duke, which did not admit its first Black undergraduates until 1963, had been designed by a Black man who would not have been welcome on the quads he created.

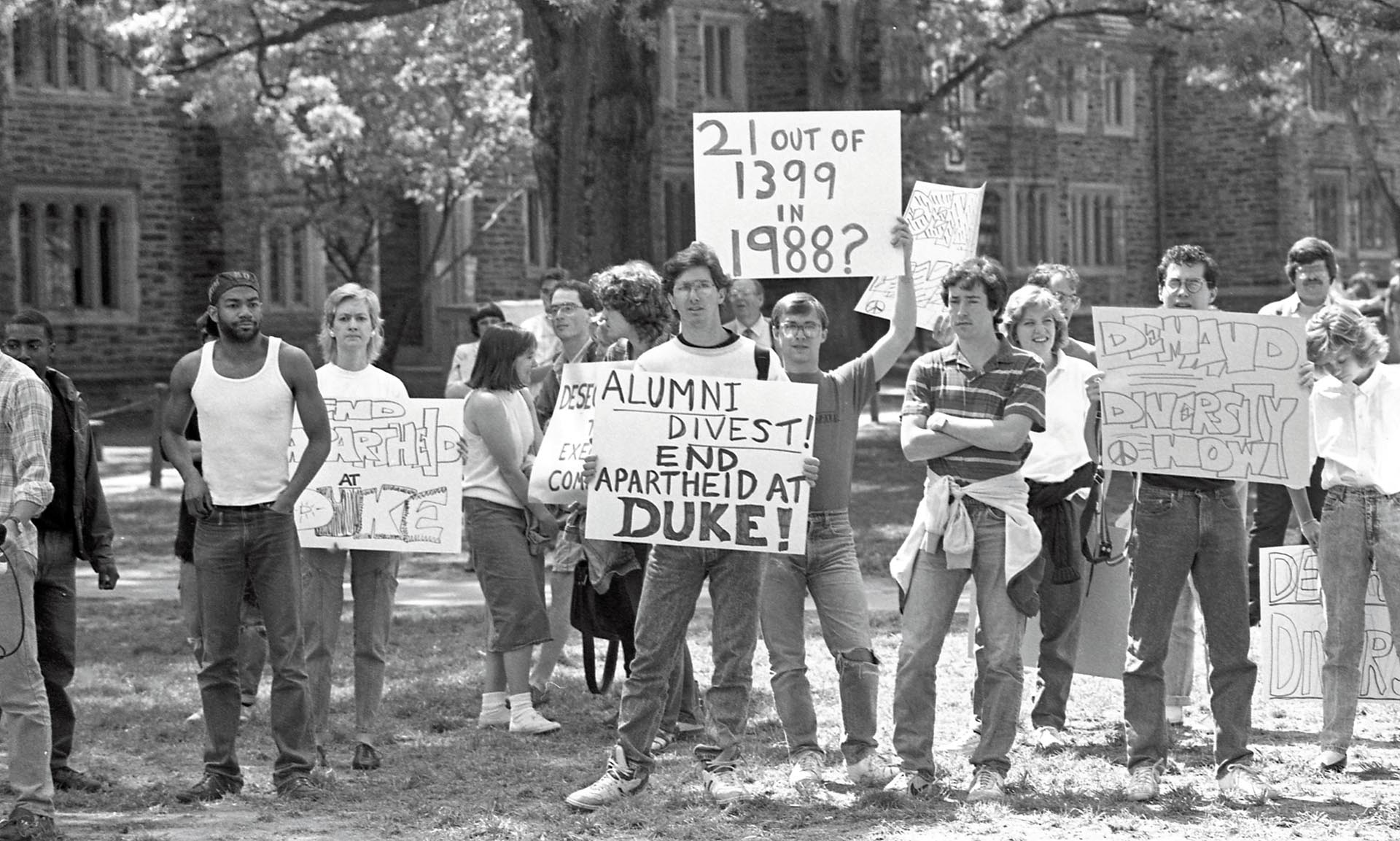

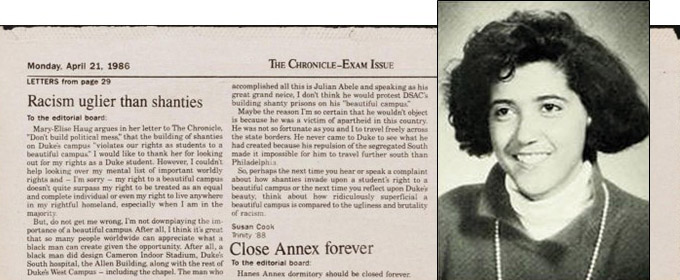

Cook’s vehicle was The Chronicle, where late in her sophomore year she replied to a letter to the editor. Students urging university divestiture from companies profiting from South African apartheid had built a shantytown on the main quad to coincide with a spring meeting of Duke’s board of trustees. A student had written to The Chronicle complaining that the protest structures violated “our rights as students to a beautiful campus.”

Says Cook, “I just remember sitting in the library with some friends and we’re just like, ‘A right to a beautiful campus? That’s nonsensical.’” And she wrote her letter, in which she noted that architect Julian Abele, the designer of West Campus, would not object to the protest because “he was a victim of apartheid in this country” and likely never visited Duke “because of his repulsion of the segregated South.” She knew whereof she spoke, she said, because she was “speaking as his great-grandniece.”

Her letter shook things up. And although it took time, Duke not only embraced Abele but used its history of participating in racism as an opportunity for reflection, ultimately renaming the main quad in his memory. Perhaps equally important, in May 1986, the Duke Board of Trustees voted to divest from companies profiting from apartheid – a rethinking of its own racism and a response to a successful protest, two elements that have become part of Duke.

Duke did not desegregate until its first Black students entered in 1961. But individuals attempted to end racism well before that. In 1948 Divinity School students unsuccessfully petitioned the school to admit Blacks. Around 1960 biochemist William Lynn Jr. repeatedly removed the words “whites only” from research building toilet doors, protected by colleagues who refused to identify him to administrators who repainted the words. Then, in 1961, the Board of Trustees voted to admit Blacks to graduate and professional schools, and in 1963, Duke admitted Black undergraduates.

“Wilhelmina was the only one from out of state,” recalls Rear Admiral Gene Kendall, one of the First Five, as the group of black undergraduates came to be remembered. He was referring to Wilhelmina Reuben-Cooke, known to Duke because her father, Odell Richardson Reuben, was studying for his Ph.D. in the Divinity School. “The decision to desegregate happened early in summer, and suddenly there we were,” recalls Kendall, who eventually graduated from the University of Kansas.

“They were earnest in what they were trying to do,” Kendall says of the Duke of the early 1960s. But by 1966, as more Black students enrolled, protests took place related to services those students needed and perspectives they brought. The few Black students often felt separated and alone, said Chuck Hopkins ’69. To draw attention to their needs, the Afro-American Society organized study-ins at the president’s office and demanded he resign from a segregated country club; Duke resisted.

In 1968, after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., more than a thousand students congregated on the quad in a Silent Vigil to mourn King and to call for more Black faculty and for better treatment of the largely Black nonacademic employees who often looked out for the Black students. Students marched to the house of President Douglas M. Knight, where they stayed for days, then returned to the quad. By the time the protest ended, the university had agreed to a raise for the nonacademic employees, but there was little improvement for Black students.

In 1969, students from the Afro-American Society briefly occupied one floor of the Allen Building (coincidentally the last building designed by Julian Abele), with demands including more support for Black students, increased Black enrollment, more black faculty, and an African-American Studies department. The students left the building just as police stormed in another door, but a crowd of mostly white students gathered outside was sprayed with tear gas by police in an engagement that lasted hours.

The Allen Building takeover brought Duke a reputation as a center of protest, says Mark Pinsky ’69, who participated in those demonstrations and wrote about them for The Chronicle. “It did establish an activist identity,” he says, “and people later built on that.” And though subsequent years haven’t had as many marches or as much tear gas, “that activist impulse and social consciousness were firmly established.” He points, for example, to the late 1990s and “the wonderful anti-sweatshop movement that grew out of Duke that had a huge impact around the world.” Duke students have protested around labor issues and United States policy issues, for and against controversial visiting speakers such as Edward Teller, and they have consistently advocated for advances in Black faculty and for Black students.

Leah Abrams ’20 participated in one of Duke’s more recent actions, the 2018 People’s State of the University protest, which, consciously honoring the tradition of the 50th anniversary of the Silent Vigil, took place during an alumni event. Some alumni and administrators weren’t happy, but then again that’s the point. “That [protest] is a unique part of Duke’s culture that comes up again and again in its protest history,” Abrams says, “and has been extremely influential in my understanding of politics outside of Duke’s campus, of politics broadly.”

But Abrams finds much about the university’s protest history that is purely Duke. “We think highly of this school,” she says of Duke student protesters, “and we think there’s a version of it that can be better and can push other universities to do the same.”

Protest or not, Duke has focused continually on its equity work. Recent years have seen Duke rename buildings once dedicated to slave owners; remove the statue of Robert E. Lee that once stood at the door of the Chapel; rename the Sociology-Psychology building for First Five member Wilhelmina Reuben-Cooke; and dedicate itself to antiracism, including the design of a universitywide course on the invention and consequences of race.

Equity at any university will always be a work in progress. But its tradition of protest should stand Duke in good stead, Pinsky says. “I was on campus recently for a John Hope Franklin symposium” on the 75th anniversary of his groundbreaking book, “From Slavery to Freedom.” On his way out, Pinsky ran into a student demonstration about Israel and Palestine. “I thought, ‘This is good.’ In the library we have a symposium for John Hope Franklin, and on the quad we have a rally of 250 students.

“I thought, ‘This is Duke.’”