In 1838, Brantley York founded and became principal of Brown’s Schoolhouse, a Randolph County private school, which the next year organized itself as the Union Institute. In 1841, Braxton Craven joined as a student and teacher, becoming principal in 1842 and remaining in charge until his death in 1882. At that point, the school had become Normal College, licensing teachers starting in 1853. In 1859, the school began receiving support from the Methodist Church and renamed itself Trinity College, adopting the motto “Eruditio et Religio” – meaning “erudition and religion.” Marquis Lafayette Wood, an alumnus, became president in 1883. In 1887 John F. Crowell began serving; he moved the institution to Durham and founded and coached its first football team. John C. Kilgo took over in 1894; he banned football, intensified the school’s aspirations toward a national reputation and strengthened its friendship with a local industrialist who had provided money to relocate the school to Durham. That donor soon gave more money, on the grounds that the relocated college admit women “on equal footing with men.” His name was Washington Duke.

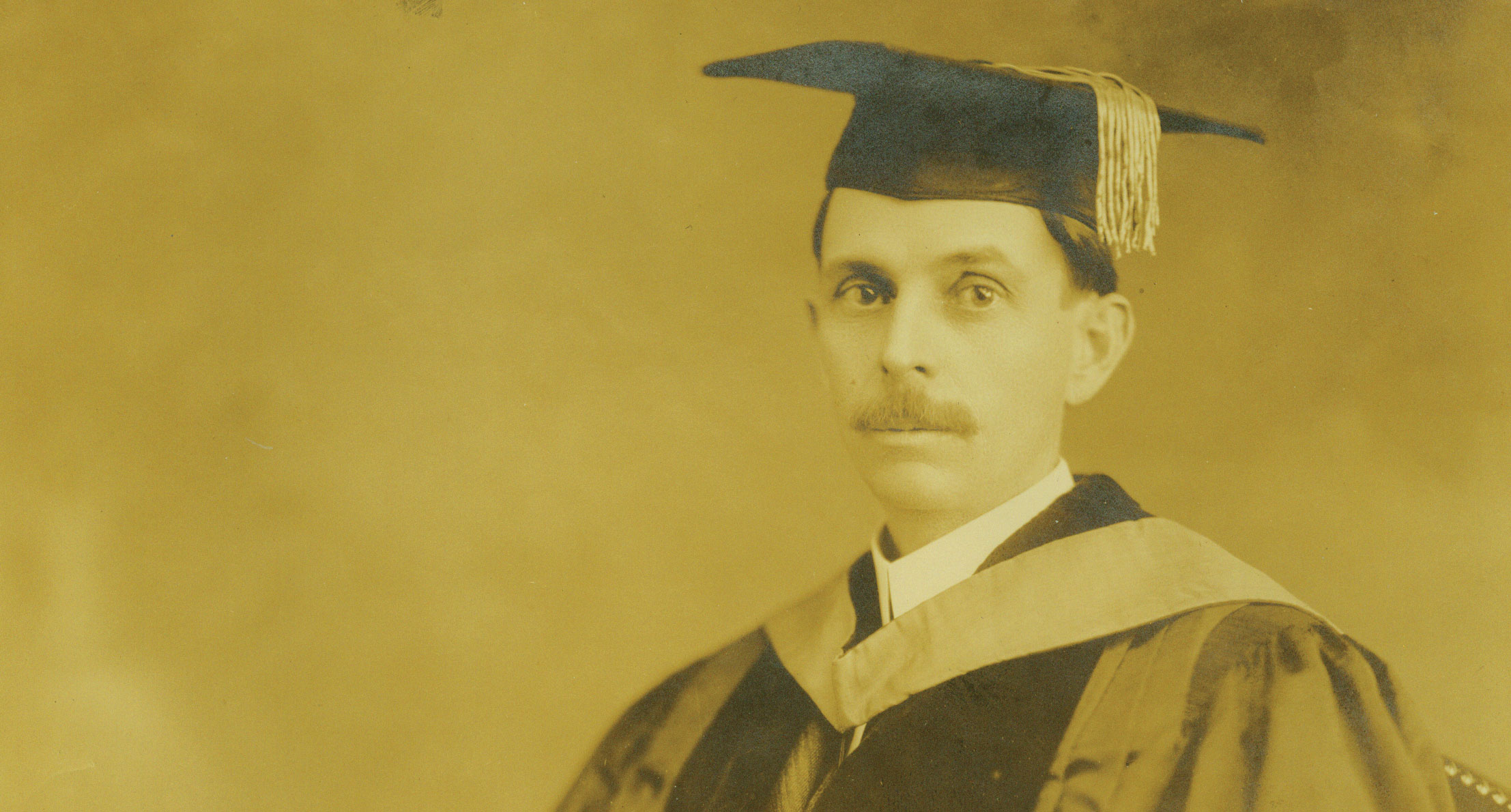

1. William Preston Few (President 1910-1940)

In 1896, Trinity College was growing comfortable in its new home in Durham, with about 400 students and 40 professors. When its only professor of English took a year’s leave of absence, President John Kilgo found a temporary replacement in a slim and frail young teacher from South Carolina with a newly minted Ph.D. from Harvard; his name was William Preston Few. That year Kilgo saw in Few “a man of superior ability” despite his natural shyness, and asked donor Benjamin Newton Duke to provide for Few’s salary so Trinity could hang onto him. Duke complied and Few stayed, eventually becoming Trinity’s first dean. When in 1903 professor John Spencer Bassett was pressured to resign after publishing an article that addressed racism and praised Booker T. Washington – Washington had spoken on campus during Few’s first weeks – Few wrote the defense of academic freedom that convinced the trustees to refuse Bassett’s resignation.

Harvard and other colleges were then forging the development of the modern research university, with its focus on research and graduate-level education. Few brought this idea with him to Trinity and the South. At that point there was “no well developed Graduate School of Arts [and Sciences],” according to a letter Few received in 1927 from a member of the Rockefeller Foundation. It was Few who suggested to James B. Duke the creation of the Duke Endowment and its transition of Trinity into a university bearing the Duke name.

As first president of the new university Few worked to create a Duke that would address that problem: Duke included plans for a graduate school of arts and sciences in the Indenture of Trust by which the university was founded. When James Buchanan Duke sought additional land on which to build that new university, it was Few, walking west of what is now East Campus, who realized what he saw: “It was for me a thrilling moment,” he wrote, “when I stood on a hill … and realized that here at last is the land we have been looking for.”

Few described himself as “an invalid boy,” but helping midwife Duke into existence evidently agreed with him: “Until about 1924 I had bad health all my life,” he wrote. In his 16 years as president Few managed the building of two campuses, the gathering of books to create libraries, and the hiring of faculty to turn homey little Trinity into the research university he and the Dukes envisioned. The School of Religion (now Divinity) and the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences were both founded in 1926. Under Few’s leadership Duke opened the Schools of Medicine (1930) and of Nursing (1931), the School of Forestry (1938, now the Nicholas School of the Environment), the College of Engineering (1938, now the Pratt School of Engineering) and the Sarah P. Duke Gardens (1939). Founder’s Day and Homecoming became traditions during Few’s time, and Duke joined the American Association of Universities – and celebrated its first centennial, commemorating one hundred years since its 1838 founding.

Both James Buchanan and Benjamin Newton Duke had died by 1929; Few is entombed with them in Duke Chapel. But they left Duke in good hands. Few knew it himself. “Then after all, my dream and your dream is to be realized in full,” he had written to Benjamin Duke in 1924. “Isn’t it glorious?”

2. Robert L. Flowers (President, 1941-1948)

“Professor Bobby Flowers,” as he was known to students, began working for Trinity College while it was still in Randolph County. One of only four professors to make the move, Flowers taught math and electrical engineering and also wired the new buildings after the move to Durham. He helped guide the purchase of the land that became West Campus and Duke Forest, and his six decades of service to Duke made him an able steward during the complex war years.

3. A. Hollis Edens (President, 1949-1960)

Duke’s first leader hired from outside, Edens took over an institution struggling to keep up with postwar inflation and changing academic needs. More, he said, “the magnitude of James B. Duke's Indenture had been such as to encourage the uninformed public to believe that Duke University never would require additional capital.” It did. He chose as chief academic officer longtime chemistry professor and dean Paul Gross. Although the two worked together well, ultimately Gross felt Edens was not effectively leading the university into the future of national recognition it hoped for, and conflict between the two led to Edens’s resignation and Gross’s return to purely faculty work. Though his term ended unhappily, Edens also fought for academic freedom during the McCarthy era, and his dispute with Gross led to better relations with the Duke Endowment and better faculty governance at Duke. And the friction was productive – the “Gross-Edens Affair” ultimately positioned Duke to advance into the top-level international institution it has become.

4. J. Deryl Hart (President, 1961-1963)

Hart was an esteemed surgeon Duke poached from Johns Hopkins when the School of Medicine began teaching in 1930. He introduced ultraviolet lights into operating rooms, drastically reducing postoperative infections, and served the School of Medicine until he became university president. During Hart’s tenure, the Board of Trustees voted in 1961 to admit the first Black graduate students, and then in 1962, Black undergrads. The home built for him in 1934 is now the official president’s residence. He and his wife, Mary, are entombed in Duke Chapel.

5. Douglas M. Knight (President, 1963-1969)

President when the first five Black undergraduate students entered Duke in 1963, Knight presided over the decidedly complicated years that followed. Considered an able and kind man overwhelmed by events, he eventually resigned after the famous Allen Building takeover by frustrated Black students. He also dedicated a building to Duke’s first art museum and presided over a major addition to Perkins Library. The school of business, now the Fuqua School of Business, was founded in 1969 during his tenure. Knight House, a modernist house he commissioned, is now used as university event space.

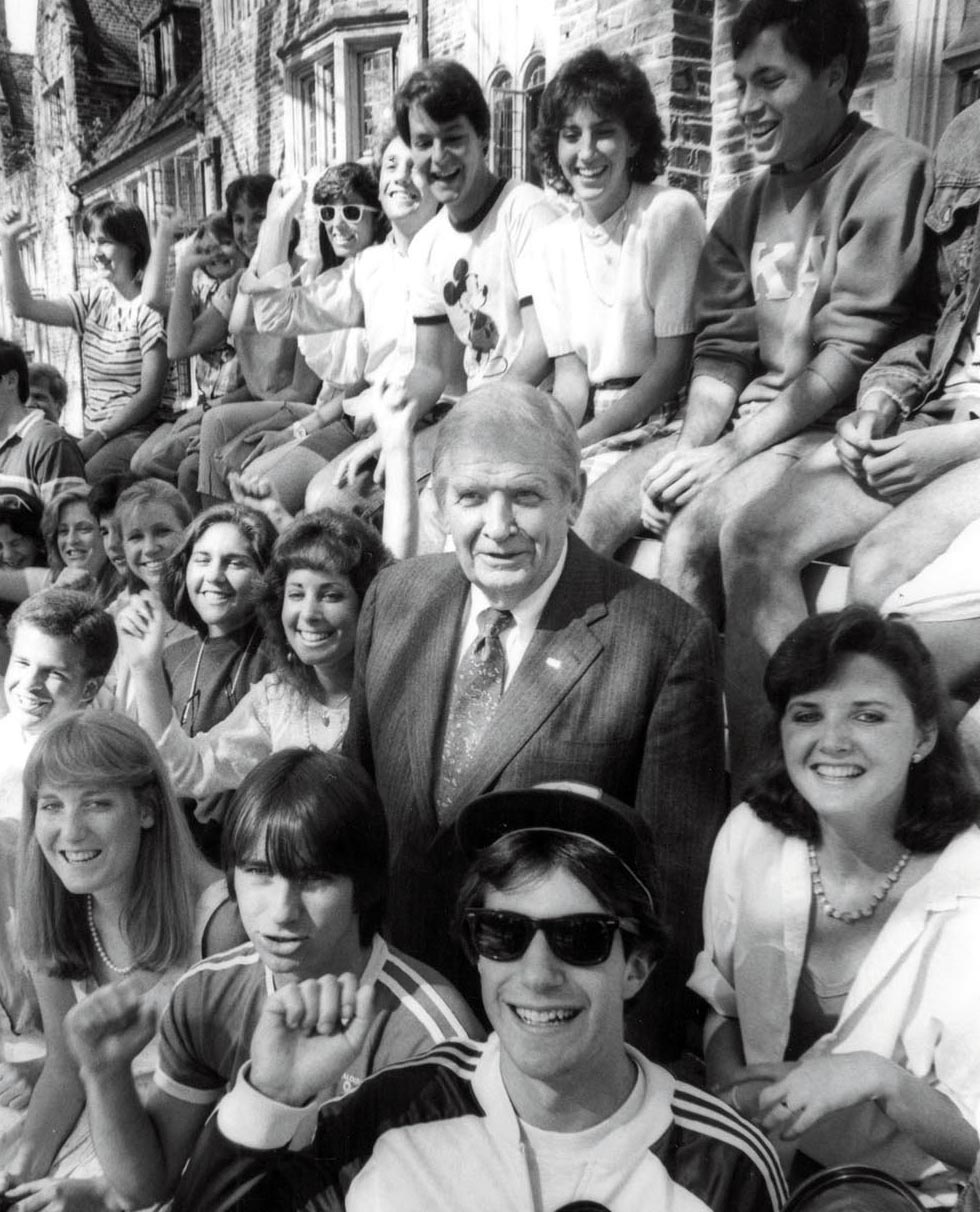

6. Terry Sanford (President 1969-1985)

“Uncle Terry” Sanford could not have been better suited to lead Duke out of the 1960s. Sanford had served as governor of North Carolina during that turbulent period, and the gentility and patient resolve that guided him then proved perfect for the tense moment when he became Duke president. A large protest in response to the Kent State shootings took place during Sanford’s first weeks at Duke. “I understood crowds and mobs and demonstrations from having been governor at the very toughest period of demonstrations,” Sanford said, “and I knew the way to handle the students was to be one of them.” He grabbed a bullhorn and urged the students to fight against the war, not Duke. And when students threatened to occupy the Allen Building, he said, “Take me with you; I’ve been trying to occupy it for a month.” A love affair was born. He soon further cemented his connection to the students by bringing a student representative onto the Board of Trustees.

Once he did occupy his Allen Building office, Sanford became Duke’s most important president since William Few. He established the Institute of Policy Sciences and Public Affairs (since renamed for him as the Sanford School of Public Policy). He opened the Mary Lou Williams Center for Black Culture. He removed the last vestiges of separation of women on campus, overseeing the formalization of women’s sports under Title IX, merging the Woman’s College with Trinity College, and establishing the Women’s Studies program. Among 40 new buildings on campus were the Bryan Center and the Mary Duke Biddle Music Building . Sanford also stabilized the school’s finances, increasing alumni giving by a factor of eight and nearly tripling the endowment.

But he is best remembered for his ability to connect with the entire Duke community, especially the students. Duke basketball fans, always fierce, had developed a national reputation for taunting that had grown obscene and unkind. Sanford finally wrote what he called “An Avuncular Letter,” urging students to “Think of something clever but clean, devastating but decent, mean but wholesome, witty and forceful but G-rated for television, and try it at the next game.” He signed the letter “Uncle Terry,” and the clever – and clean – taunts at the next game raised the level of what are now the Cameron Crazies.

Even more famous than “Uncle Terry,” though, is the phrase “outrageous ambition,” the theme of his final address to faculty in 1984. What had still been a university with an excellent regional reputation when Sanford took office, he said, ought to aim for the highest levels of achievement. He harkened back to President Crowell’s taking the chance to move Trinity College to Durham: “Decisions have long lives,” he said. “Think what the situation would have been … had it not been for Crowell’s outrageous ambition.” He finished with a vision for Duke that has guided it ever since: “Duke aspires to leave its students with an abiding concern for justice, with a resolve for compassion and concern for others, with minds unfettered by racial and other prejudices, with a dedication to service to society, with an intellectual sharpness, and with an ability to think straight now and throughout life. All of these goals are worthy of outrageous ambitions.”

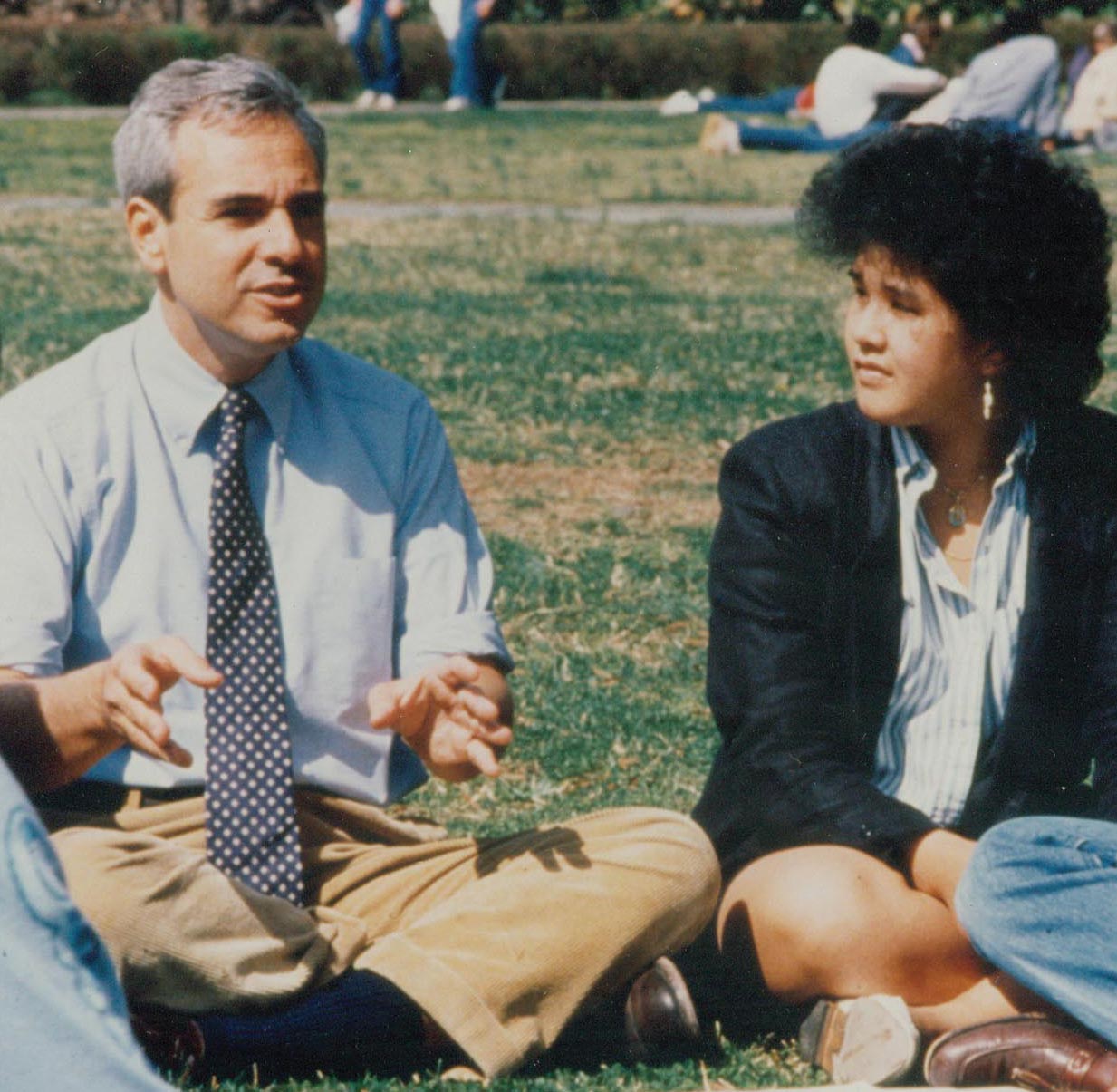

7. H. Keith H. Brodie (President, 1985-1993)

Brodie took over a university still glowing from the presidency of Terry Sanford, and during his tenure Duke continued its rise in prestige and notoriety. He worked to significantly increase applications for admission, both for undergraduate and graduate schools, and to expand the university focus on diversity and interdisciplinary scholarship, creating the Black Faculty Initiative and the Women’s Center. During Brodie’s term, Duke won its first NCAA championships: men’s soccer in 1986 and men’s basketball in 1991 and 1992.

8: Nannerl Keohane (President 1993-2004)

“I think women have always felt that we’re really a part of Duke,” says Nan Keohane. “Not just an add-on.” Joining Duke after more than a decade as president of all-women’s Wellesley College, Keohane knew that Duke had embraced educating women far earlier than many of its peers (as a result of Washington Duke’s 1896 gift predicated on the school placing women “on an equal footing with men”). Still, she was Duke’s first woman president, and she noticed. One of her first challenges was to settle an already brewing controversy. East Campus had ceased being the women’s campus in 1972, and in 1993 Duke considered turning it entirely over to first-year students. Feelings ran strong, and when she and the Board of Trustees ultimately chose to embrace the freshman campus, one sign she saw said, “Nan is ruining Duke.” She doubted a male president would have been called by his first name.

It didn’t worry her. During her tenure, women advanced throughout Duke: The Law School appointed a female dean and the Pratt School of Engineering granted its first tenure to a female professor and appointed its first female dean. The women’s golf team even became the first Duke women’s team to win a national championship. And to keep the spirit of the Woman’s College (which merged with Trinity in 1972), Keohane in 2002 launched the Women’s Initiative, which addressed women’s issues on campus for students, staff and faculty. She worked to steer student culture away from alcohol and fraternities, and the decision to focus East Campus on freshmen has become one of Duke’s beloved traditions.

When Keohane arrived in Durham, the smell of tobacco still emanated from a few remaining warehouses. Long before her term was over tobacco was utterly gone, and Durham’s shattered downtown was one of her priorities. When developers began planning to renovate the American Tobacco Campus, long fallen into disrepair, Keohane – along with longtime Duke executive vice president Tallman Trask – committed Duke to renting part of the project, encouraging further investors and propelling its success. The Duke-Durham Neighborhood Partnership, started in 1996, has fostered continued improvements in Duke’s relationship with its host city.

Keohane may have left her largest mark on Duke through her focus on interdisciplinarity – the effort to move professors and students out of departments and into the cross-departmental collaboration for which Duke is now recognized. What makes it work, she says, is focus. “Interdisciplinarity can be kind of messy and unfocused,” she says; programs like the Kenan Institute for Ethics and the Bass Society of Fellows, subsidizing cross-disciplinary research and teaching, and the Robertson Scholars program, which stretched that cooperation even to the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill (all three programs supported by namesake benefactors) organized and honed the interdisciplinary work. “It’s not just sort of kumbaya.”

Keohane also presided over a reorganization of Duke Health and a campus building boom, including a significant renovation of the athletic complex. Often seen at not just big-ticket events but events like field hockey games (sometimes with her grandchildren), Keohane saw the explosion in Duke athletic prowess that has become part of Duke’s secret sauce. “Duke has something those other schools just don’t have,” she says. “A distinctive sort of fan obsession. A kind of spur – an excitement. That’s Duke.”

9. Richard Brodhead (President, 2004-2017)

Soon after Dick Brodhead took over from Nan Keohane, he had to manage Duke through the fraught and complex lacrosse scandal, in which three members of the men’s lacrosse team were accused of rape by a sex worker. The charges turned out to be false, but the accusation and Duke’s response led to a rethinking of the culture surrounding the sport (ultimately followed by three NCAA championships). Brodhead’s term saw an expanding commitment to the city of Durham and the creation of Duke Engage, which has become one of Duke’s signature programs, in which students spend a summer collaborating with a team of faculty and local leaders to learn about the process of addressing a real-world problem. Brodhead also oversaw the radical renovation of West Union and Duke’s international expansion with the creation of Duke Kunshan University and Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore. He also was the most recent president to enjoy a Duke NCAA basketball championship.

10. Vincent Price (President, 2017-present)

Joining Duke in 2017, Vince Price has used long-term goals to steer the university’s response to emergent crises. The “Black Lives Matter” movement helped lead Duke to adopt a policy of antiracism throughout the university, even in curriculum, where a class open to the entire university addresses the invention and consequences of race. A similar universitywide class discusses climate change, which Duke has responded to with its Climate Commitment. Through that, Duke pledges to address the climate crisis in its actions, research and teaching. Price has advanced Duke’s focus on both science and technology and the arts, and Duke has continued its improvement on the student experience with the QuadEx program linking East and West campuses.