A jet-lagged Charlie Thompson stood on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial and gazed out over the Reflecting Pool.

Days earlier he had been in Spain, where he walked the 500-mile Camino de Santiago pilgrimage, which leads to the reputed resting place of the apostle St. James. On the return flight, Thompson had wondered whether the United States had its own sacred sites. Upon landing at RDU, he spontaneously joined a book group’s Washington trip, departing days later. There, Thompson found himself below the enormous Abraham Lincoln monument, on a sunny May afternoon in 2016, thinking that yes, America did have sacred sites. Gettysburg, the battlefield where Lincoln gave his iconic address, crossed his mind as one. And then Thompson looked at the steps themselves.

“There’s a plaque that says, ‘Right here is where Martin Luther King stood to give his ‘I Have a Dream’ speech,’” Thompson says with undisguised awe. “This young man from Africa was filming that. I thought yes, people make pilgrimages to these sites.”

“We became friends and colleagues. Not only that: Co-conspirators is a great way to put it.”

Charlie Thompson

Thompson, a professor of the practice of cultural anthropology and documentary studies and senior fellow at the Kenan Institute for Ethics, realized there were sacred sites nationwide, both well-known and obscure. Many of these are sites of struggle or suffering. He thought of Selma, Alabama, and the Civil Rights Movement. He thought of World War II Japanese internment camps in the western United States. Even a strip mall parking lot, he posits, could have been where an indigenous group was wiped out. Just dig into the soil, study the history, he says. These sites are everywhere.

Together with his playwright and actor friend Mike Wiley, the Kenan Institute’s artist in residence, Thompson launched America’s Hallowed Ground in 2022. This project blends documentary and the arts – which co-directors Thompson and Wiley assert are one and the same – to tell the stories of sites of struggle, particularly those with an element of racial inequality. The two started in North Carolina and chose Cherokee, with a focus on the 1838 Trail of Tears, and Wilmington, where a white supremacist mob massacred Black citizens and overthrew a legally elected, racially integrated government in 1898.

Wiley, a dramatist, and Thompson, a documentarian, are storytellers. They believe that art makes history accessible and memorable to the broader public. Through America’s Hallowed Ground, they want to pass skills of documentary-as-art to the people whose ancestors struggled in Wilmington, Cherokee – anywhere.

“How do we convince people that they are the holders of history … that everybody is responsible for always preserving the story?” Thompson asks. “All of us are called to be co-creators of this country, and art is the way we tell ourselves that. It’s how we see the message. It reaches our hearts in ways I am continually amazed by.”

Thompson and Wiley are finishing lunch outside the Durham Whole Foods while a gray drizzle falls on East Campus. Conversation veers from work to family to everyday concerns with the easy, familiar tempo of cousins shooting the breeze, which these two might as well be. Both were born in Roanoke, Virginia – Thompson in 1956 and Wiley in 1972 – and both their families are from the same part of the Virginia mountains.

“If we went on a spiritual level, we might have been in the works before we knew each other,” Wiley says.

In the real world, they met in 2007. Thompson, formerly with the Center for Documentary Studies, was then curriculum and education director for The South in Black and White, an ambitious Duke-led multi-university and community course, with students attending from Duke, North Carolina Central University and the University of North Carolina. As part of the course, Wiley performed “Dar He,” his solo show about Emmett Till.

“We became friends and colleagues,” Thompson says. “Not only that: Co-conspirators is a great way to put it.”

By 2010 (and again in 2014) Wiley was the Lehman Brady Joint Visiting Professor of Documentary Studies at Duke and UNC. He taught a course about the Freedom Riders of 1961, who challenged segregation on interstate buses and in bus terminals. Soon Wiley had a play about the subject, “The Parchman Hour,” which led to a 2011 Mississippi trip to visit the sites of the Freedom Riders’ struggle. Students, a band of teenage musicians, Wiley, Thompson, and “Blood Done Sign My Name” author Tim Tyson all boarded a late-night bus from Duke and traveled to key Civil Rights Movement sites.

“It felt like we were on a freedom ride,” says Thompson.

During the height of the COVID pandemic, Thompson and Wiley sat down for coffee at an outdoor patio in Pittsboro, North Carolina, where Wiley lives and Thompson once did, to brainstorm how to capture that lightning again.

“All of us are called to be co-creators of this country, and art is the way we tell ourselves that. It’s how we see the message. It reaches our hearts in ways I am continually amazed by.”

Charlie Thompson

On the morning of March 4, a chartered van pulls up to DREAMS of Wilmington, a youth center not far from the graveyard where Black residents hid from a white mob that destroyed Black economic and political power in the city in 1898, as described in books like David Zucchino’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “Wilmington’s Lie” and films such as Christopher Everett’s documentary “Wilmington on Fire.” A century and a quarter later, Wilmington is starkly segregated, racially and economically. Just blocks from the humble houses that surround DREAMS, the Wilmington Riverwalk awaits weekend crowds on this warm late-winter Saturday.

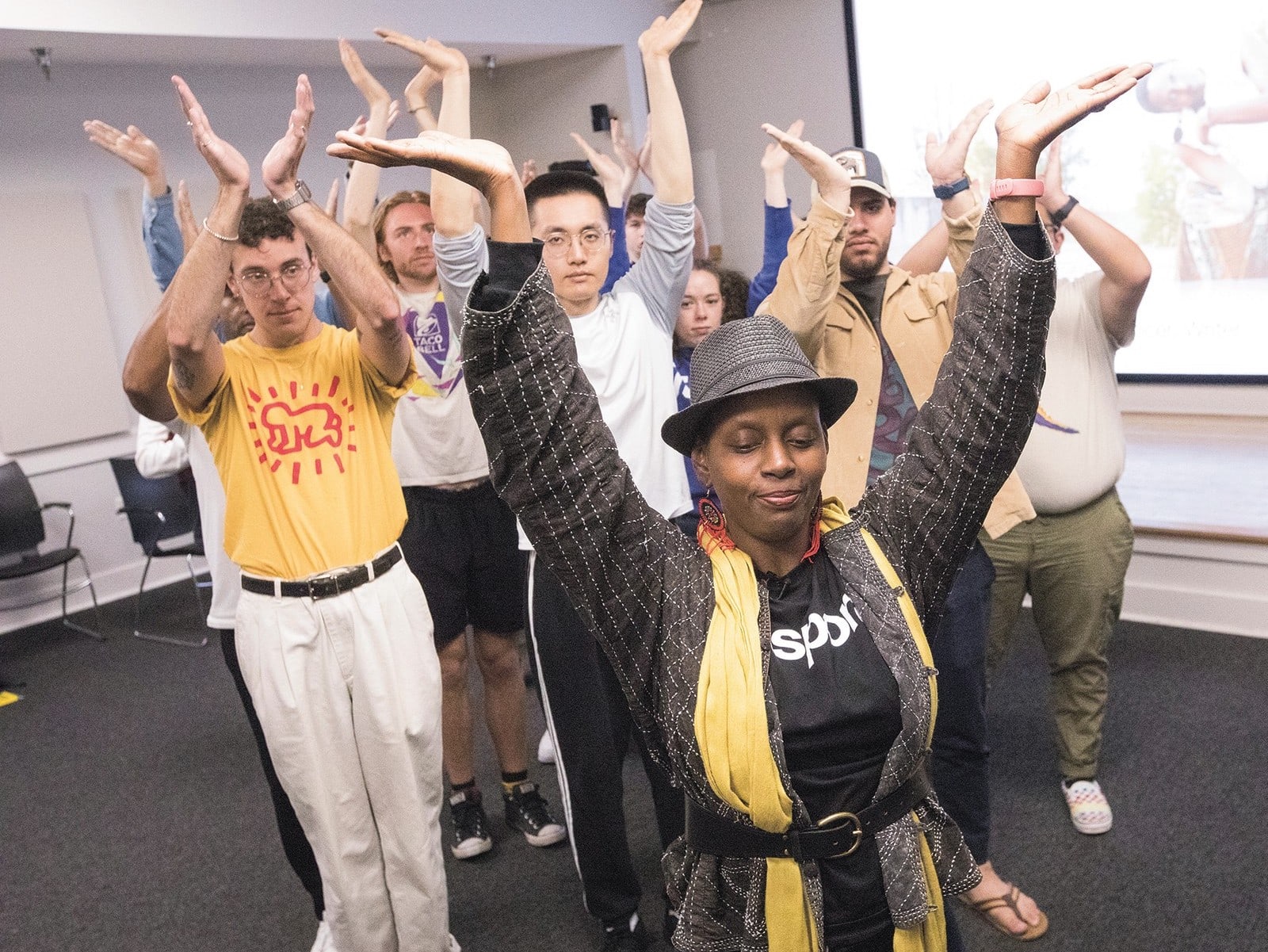

A dozen Duke students, from Thompson and Wiley’s spring ’23 Fieldwork Methods: America’s Hallowed Ground course, step out of the van. Inside DREAMS, Thompson and Wiley have gathered artists from a broad swath of disciplines: North Carolina Poet Laureate Jaki Shelton Green, movement artist Aya Shabu, muralist Cornelio Campos, playwright Howard L. Craft, songwriter Laurelyn Dossett and podcasters John Biewen and Michael Betts II. The Duke students are quickly immersed in a crowd of Wilmington artists and educators, the latter of whom have come to learn how to talk to their own classes about the 1898 coup.

In a small instrument-filled room used to teach music to neighborhood children, Dossett leads a group of educators, Wilmington locals and Duke students in the art and practice of authentically portraying location, era and character. Together, they flesh out a fictional woman who could be the subject of a historically accurate song.

“There are certain techniques to set time and place,” says Dossett.

Dossett and Wiley first worked together in the 2018 play “Leaving Eden.” The play shares its name with a Dossett-penned song, which the Carolina Chocolate Drops made the title track of their fourth album in 2012. The “Leaving Eden” play told a story of race and power in rural North Carolina. In part, the play’s historical narrative fictionalized the 1898 Wilmington massacre. Its contemporary arc focused on a modern Latinx community.

At DREAMS, Dossett plays some of her songs to demonstrate how they fit within the structure of that play and how imagery, tempo or guitar tunings can create a believable song-world. Down the hall, Biewen and Betts impart interviewing techniques. Through another door, Green guides participants through a deep dive of their own psyches.

At the end of the day, the local artists present to the larger group. A woman from one of Craft’s sessions reads a fiery poem she composed in less than an hour. Wilmington middle school teachers talk about race and inequity. Shabu’s presentation, in the form of expressive movement, includes a Duke student mirroring a DREAMS dance instructor as they fall in shock and flow along the floor, unselfconscious. And then the America’s Hallowed Ground workshops end with a benediction of sorts, with all the artists – Black, white, Latino – leading the room in the folk spiritual “Meeting at the Building.”

“If you have partners in these sorts of paths, it makes us braver to not have to do it alone,” Dossett says.

"I had a moment after the Wilmington trip [in 2022],” says Rachel Kamis, referring to an earlier America’s Hallowed Ground trip to the coastal city, “[when I thought] I don’t understand where I’m from. I need to look into the history.”

Kamis, a cultural anthropology major, took the spring ’22 section of Fieldwork Methods: America’s Hallowed Ground, co-taught by Thompson and Wiley. She returned in spring ’23 as student assistant. The Bethesda, Maryland-raised Kamis has traveled to Wilmington twice with the course and to Cherokee once. She gained an appreciation for the way the history of a place echoes in its modern communities, and the way artists fit in that equation.

“Art gets at your heartstrings and your empathy,” Kamis says. “It forces you to think about who you are and how you act in the world.”

In America’s Hallowed Ground and in his earlier work, Thompson has purposefully introduced students to artists who do their work in and with communities. Art is a language anyone can understand, he says, and it can make history seem real and immediate. Wiley thinks back to the 2011 Mississippi trip, when he performed “The Parchman Hour” at the poorest school in the poorest district in the state, as he puts it. He saw the power of art as documentary – or documentary as art – in the appreciation these Mississippi schoolchildren had for the history of struggle in their own figurative back yards.

“Charlie’s documentary work, my theater work, it is in many ways this bridge between people,” Wiley says. “It also can be an entryway for people to see themselves in history.”