Duke University is making a commitment to understanding and solving climate change impacts, and one of the most visible signs of climate change is the rise in sea levels. Greenland, in particular, is experiencing a rapid melt of its glacial ice, which has global consequences. Here in the University Archives, a diary kept by professor Henry Oosting documents an extraordinary arctic voyage to Greenland in 1937.

Oosting joined Duke as a professor in 1932 and spent the rest of his career, more than 30 years, in the botany department, serving as chair for 12 years. His interests were in vegetation, particularly of the southeast, and old growth forests, but early in his career at Duke, he was invited to accompany philanthropist, photographer, and polar explorer Louise A. Boyd on a voyage to eastern Greenland, sponsored by the American Geographical Society. Boyd had made several voyages to Greenland and Arctic areas. She hired a crew and some scientists to board the Veslekari, a wooden boat and a veteran of icy travel for exploration and fishing. The expedition’s primary aim was to make a “detailed study of the glacial-marginal features of the Greenland coast,” with particular emphasis on the ways the glaciers grew or receded. In addition to a botanist, there were geologists, cartographers, and photographers, and many ship hands.

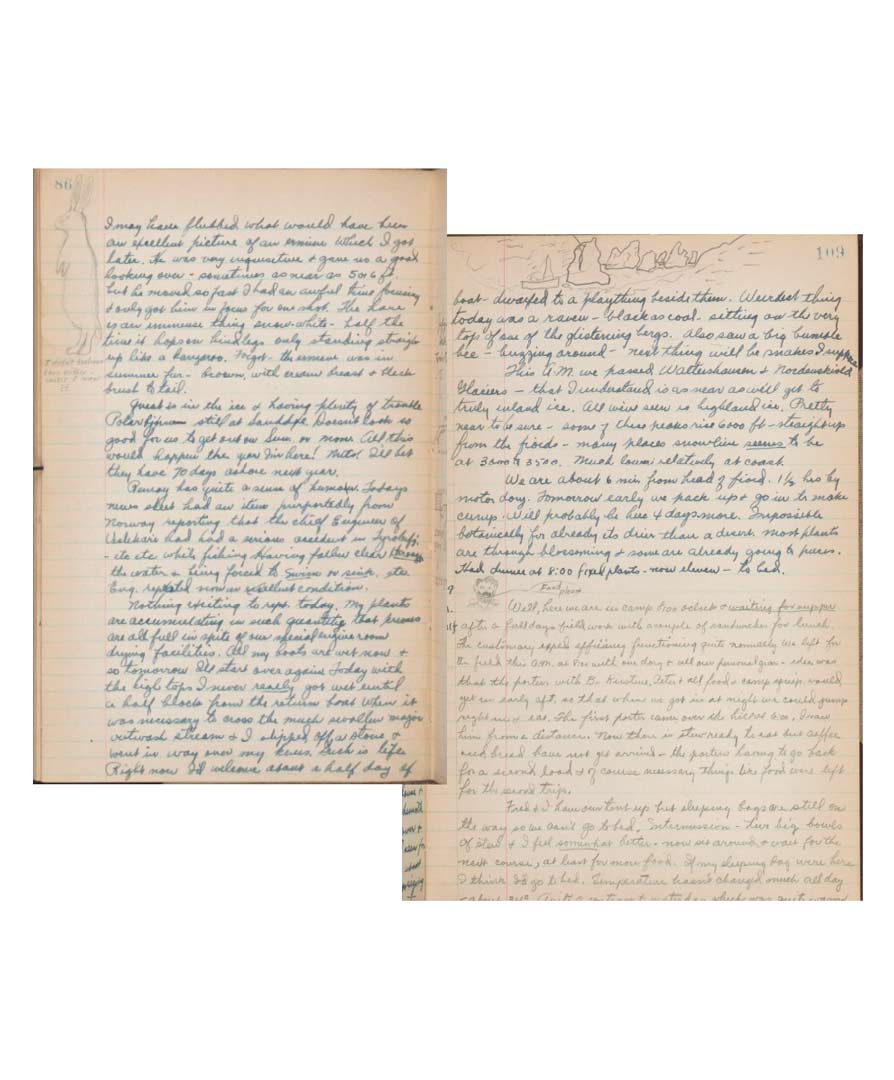

Oosting left Durham on June 9, and did not return home until Sept. 21, 1937. In between those dates, Oosting kept a diary describing the activities, sights and experiences of the trip, along with many hand-drawn illustrations of what he had seen. He addresses many of the entries to “Cornie,” his wife Cornelia. Inside the front cover, he states that he is keeping the diary to share the experience with her, and to keep himself entertained. “These are the reasons which may then help to explain what may appear to be the inane mental ramblings of a simple-minded botanist.”

After sailing from New York and making their way up to Norway, the crew set sail for Greenland on June 30. They stopped on the small volcanic island of Jan Mayen, with the relatively tropical temperature of 7 or 8 degrees Celsius (around 45 degrees Fahrenheit). As the ship continued to make its way northwest to Greenland, the temperature dropped to freezing, and those on the Veslekari felt thumps as the boat encountered icebergs.

“The scientific contribution cannot, by the widest stretch of imagination, amount to a ‘hoot.’”

Henry Oosting

Oosting’s notes about Greenland are remarkable. Among the creatures he saw were musk oxen, polar bears, seals, walruses, foxes, hares and even a whale. A typical entry from Aug. 6, when they were on the Franz Joseph Fjord, includes notes about flora, fauna and geologic features.

Went ashore this a.m. (8:00) at Ovibos Cape. A great barren dolomitic that looked decidedly unpromising – but after we got started – collected more [specimens] of [flowering] plants by noon than ever before. Tiny little Erigeron [daisy] no more than ½ in. high had 1-2 good sized [flowers] on it. Had plenty of musk ox to see for change. Think I have fairly close picture of cow and two calves. Their flowing hair and wool makes them seem to glide along. They are agile as goats + very graceful in movement. Eider family down close to shore with 10 young – scurried through water just churning it up when we came down – the little fellows were almost walking on H2O.

Later that day he added, noting that most of an iceberg is found underwater:

Perhaps I was most impressed by the immense icebergs floating about which have come from the glaciers. We passed close to one this [afternoon]. That was estimated at 130 ft. above water + that’s of course 2/7 of its size.

Some of the passages describe situations that are hard to imagine happening today. The ship’s crew enthusiastically hunted polar bears and cubs, walruses, and seals by firing rifles from the boat. Their modest quantities of game were unremarkable to the Norwegian crew, who “think that 3 or 4,000 white (baby seals) is a small catch for six weeks.” In other less-than-pleasant passages, Oosting bemoans having to tolerate a woman like Louise Boyd. “Generous and bighearted about big things,” he muses in a typical entry, “she is quite impossible about some small, petty things. Typical of most older women in scientific contacts. Further strengthens my feeling about women in science.”

At other times he writes tenderly about missing his family and Durham’s hot summer weather. He complains of the boredom of reading the same books and keeping the same company, especially when the ship is stuck in ice and unable to move until something shifts. At several points, he declares emphatically that this will be his last arctic voyage.

Escaping in August before the winter set in (but not before the boat had to dynamite its way out of the ice), Oosting finally returned to Durham. Interrupted by World War II, Boyd published a book, The Coast of Northeast Greenland, in 1948, based on two arctic research trips she took in 1937 and 1938. Oosting contributed a chapter about botanical collecting, despite his belief, while warming up after a particularly sloppy, wet and cold morning of sample gathering, that “The scientific contribution cannot, by the widest stretch of imagination, amount to a ‘hoot.’”

Here in the University Archives, the Oosting diary has been used in history classes as an example of Duke’s own history of scientific research. It is a rich source of information on glacial formation, climate and weather conditions, flora and fauna, foodways, Nordic culture, and much more. Although the trip of more than 11,000 nautical miles was a trial of patience and perseverance for Oosting, it remains a fascinating artifact of a scientist working in another time and place, documenting the past and allowing us to compare what we see today.

To explore the diary and photographs for yourself, visit https://repository.duke.edu/dc/uaoosting.