Very few people discover something so startling that they are compelled to say, “Stop the presses!” Fewer still do so while examining a nearly 300-year-old-book in a university research library.

Janet Stiles Tyson, then, is one very lucky woman.

“I ran up to the desk where the librarians were, and I just said, ‘Do you see what's in here? … ‘Do you realize what this is?’ Anyway, I was just practically hyperventilating.”

This dramatic moment came when Tyson, a researcher and writer from Michigan, visited the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library in 2022 to view Duke’s copy of a landmark book of botanical art. “A Curious Herbal, Containing Five Hundred Cuts, of the Most Useful Plants, Which Are Now Used in the Practice of Physick” was the production of Elizabeth Blackwell, an early 18th-century British illustrator and woman of science. Tyson, who researched Blackwell for her Ph.D. thesis at Birkbeck University of London, had been commissioned to write an essay for a new edition of “A Curious Herbal” and had set out to see as many of the original copies as possible.

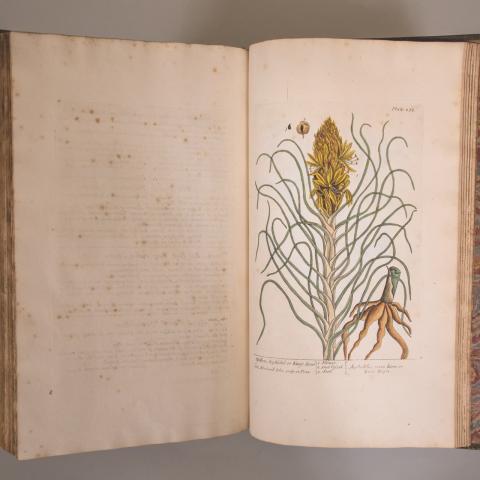

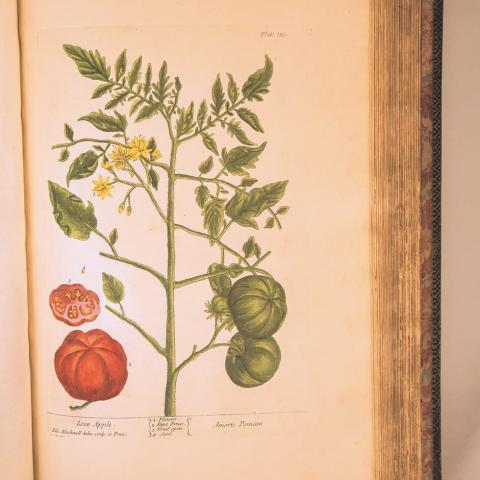

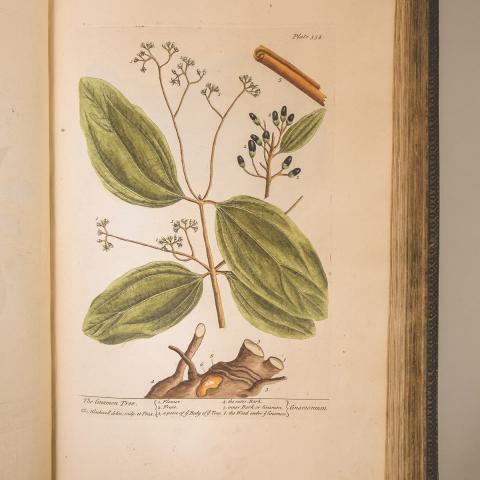

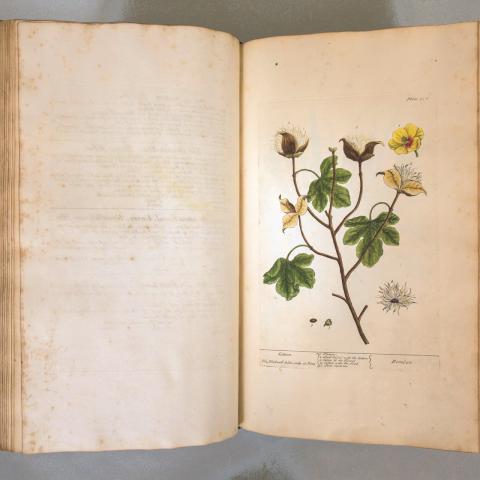

Blackwell’s creation was a pioneering work – a two-volume masterpiece containing hand-colored botanical engravings especially useful to those using plants medicinally. Volume 1 was published in London in 1737, followed by Volume 2 in 1739. The Rubenstein, which acquired its copy in 2018, didn’t just happen to purchase the book. It was part of a carefully planned collection strategy at the library.

“We have a particular interest in the lives of women,” says Andrew Armacost, head of collection development and curator of collections at the Rubenstein, referring to the Sallie Bingham Center for Women's History & Culture. The medicinal aspect of the book also made it a good fit for the library’s History of Medicine Collections.

While her masterwork has become a classic text, Blackwell, herself, was something of a cipher. Little was known of her life beyond the fact that she was married to Alexander Blackwell, a Scotsman who was fined for running a printing business without having served an apprenticeship and condemned to debtor’s prison when he couldn’t pay. It was generally believed that Elizabeth Blackwell undertook the book to support her family while her husband was in jail. She produced the engravings that became “A Curious Herbal” from 1735 to 1739 as a series of weekly fascicules – four engravings and one page of descriptive text – that subscribers would purchase from booksellers. Ultimately, when the 500 engravings were complete and purchased, readers would take their piles of pages to a binder and have them made into books.

Thus, Tyson notes, each of the more than 100 known original copies are different. Although the engravings are numbered, and so bound in a specific order, some volumes have elements differently organized or missing. “None of these copies was like any of the others,” she says. “They were all unique in one way or another.”

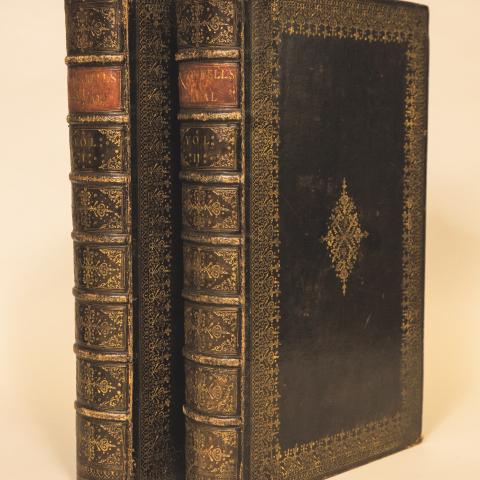

Tyson visited dozens of libraries in Europe and the U.S. to inspect their copies of “A Curious Herbal,” which brought her to Duke in August of last year. What she found is a thing of beauty. Each 18-by-12-inch gilt-edged page is printed on one side only, so the impressions of the plates that Blackwell herself engraved are visible in the thick paper. There are marbled endpapers and gold tooling on the black goatskin binding.

“Goat is the more expensive leather,” says Lauren Reno, rare materials cataloging section head at the Rubenstein.

“Books tell you sometimes how important they are,” says Armacost.

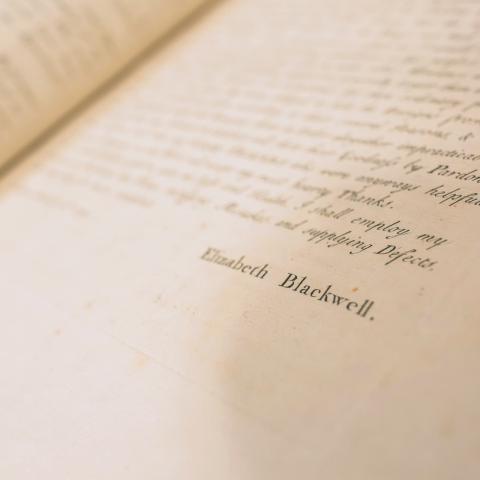

When Tyson began carefully turning the pages of the Rubenstein copy, she encountered something she had not seen before: A two-page preface, written by Blackwell and dated April 12, 1739, that revealed significant details of her life and work not previously known by scholars.

Writing about her lifelong interest in drawing, Blackwell recalled a childhood surrounded daily by “agreeable objects” due to “my father, Mr. Leonard Simpson, being a painter.” Tyson realized she was learning things hitherto unknown. Experts believed Blackwell had come from Aberdeen, Scotland, which was her husband’s home. But Blackwell’s naming of her father and his occupation provided a clue that would change the historical record. Without even leaving the library, she emailed research colleagues who were able to track down the artist Leonard Simpson and find an announcement of Blackwell’s birth in 1699, in London, in a parish record book.

Blackwell’s preface went on to describe how “A Curious Herbal” had come about, the challenges she faced in its production and the support she received from the scientific community. This was information Tyson realized she could bring to the reading public for the first time, so she called the new edition’s publisher: “I was kind of like, ‘Stop the presses. We have new information,’” she says. “And I was able to put that in.” The new edition, with Tyson’s discovery noted in her essay, was published on May 16 by the fine art publisher Abbeville Press.

“It gets at the life cycle of a rare book,” says Reno. The unique preface is just part of the story.

Worth stopping the presses, indeed.