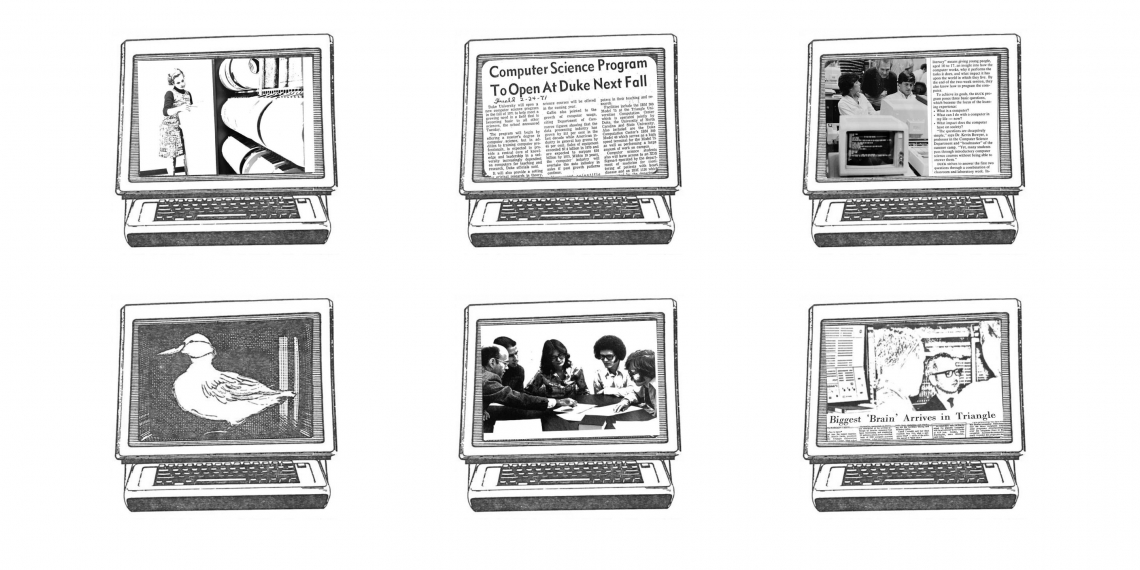

In 1975, when Craig Asplund became one of the first Duke students to graduate with a computer science major, the entire state of North Carolina had less computing power than the phone in your pocket today.

The Department of Computer Science hasn’t grown quite that exponentially, but it sometimes seems like it. Today, it boasts 43 primary faculty spanning a wide range of sub-disciplines, from theoretical computer science to artificial intelligence and computer science education. In 2023, it graduated 423 majors, making Computer Science the largest major on campus.

“Computer science nowadays is not just one department,” said Jian Pei, Arthur S. Pearse Distinguished Professor of Computer Science and chair of the department. “It penetrates every corner of our life, and it is developing in such a way that no one department can stay away from it.”

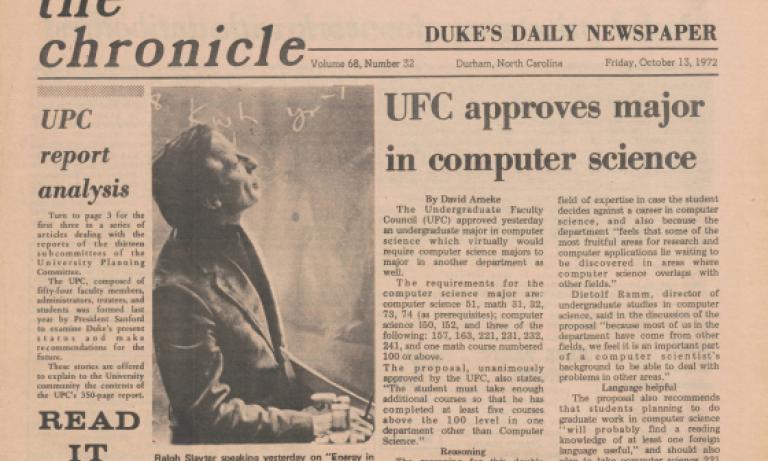

That wasn’t the case when Asplund was a student. The degree itself didn’t even exist, but he fell in love with the language after taking an Intro to Computing Programming class. When the Chronicle announced the creation of the major, in 1972, he was the first in line to sign up. The Duke Computer Science Program was promoted to the department level a year later, in 1973.

This Fall, faculty and current graduate and undergraduate students were joined by the department’s founders, as well as many of the department’s highly successful alums — such as Asplund, who worked for spent 25 years with Nokia Bell Lab and 17 years with the American Chemical Society — to celebrate its 50th anniversary.

Powering up

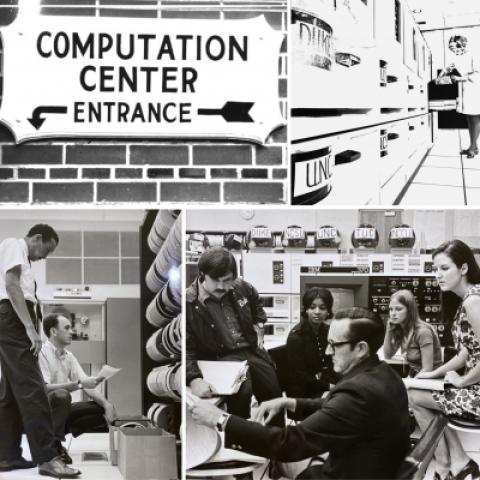

Establishing the Department of Computer Science took some convincing. More specifically, it took a push from the Dean of Medicine.

It was only when Frank Starmer — then an assistant professor in the Department of Medicine, now professor emeritus of Computer Science and one of the department’s pioneering faculty — received a competing offer from Baylor University that Computer Science at Duke began in earnest.

“The Medical Center administration was very forward thinking. They were convinced that computing would be essential in the future for medicine,” Starmer recalled. “So when the word got around that I was leaving, Bill Anlyan, who was dean, and Eugene Stead, who was the chairman of medicine, walked down to the campus to see Harold Lewis, then Dean of Arts and Sciences, and said, ‘Frank doesn't have any colleagues. And we need a computer science department today.’”

Starmer was offered an associate professor position and launched Duke’s Program in Computer Science with mathematicians Tom Gallie, Merrell Patrick and Dietolf (Dee) Ramm. Two years later, with a big financial investment from the Departments of Medicine and Surgery and the Division of Cardiology, Duke’s Department of Computer Science was officially greenlighted in 1973.

The university recruited Donald Loveland, a Carnegie Mellon professor at the time, to be the department’s first chair. He negotiated three additional faculty positions as a condition of his hire.

“The best leverage you have is when you’re coming in,” Loveland said. “I knew they wanted me.”

Evolving research

Those three positions multiplied more than ten-fold in the decades since, drastically expanding the breadth of research conducted in the department and turning it into the inescapable discipline it is today at Duke.

The rate of change isn’t constant, though. Each new tool opens doors to entire fields of research, that in turn create new areas of impact and another new set of tools. This whirlwind of progress may seem at odds with the often-glacial pace of academic research.

Pankaj Agarwal, RJR Nabisco Distinguished Professor of Computer Science in Trinity College of Arts & Sciences, a faculty member in the department since 1989, names natural language processing and AI as fields that looked drastically different three decades ago, and data mining, cyber security and data privacy as ones that either didn’t exist or were in their infancy.

To keep up, the department has had to judiciously invest in people rather than products — a philosophy that dates from its inception.

“We had to be very careful with hiring,” said Loveland about the three professorships he negotiated for the department in 1973, “so we took a relatively sharp, critical approach. When I stepped down from my chairmanship [in 1978] we still had an open position because we just couldn't find the person we wanted.”

“We want to build and expand on our strengths, so each hire should not be in a silo,” said Agarwal, who hired many of the department’s current faculty in his nine years as chair. “We should be working with each other, interacting with other faculty in other departments, so that together we are more than the sum of our individual faculty.”

The approach continually creates new interdisciplinary research opportunities. And who better to inspire that change than the future generation?

“Our students, no matter if they are undergrad or grad students, they’re the bravest people to explore new areas,” said Pei. “We’re working with them, and their research enriches our whole department, pushes the frontier and raises the profile of our research.”

Expanding the classroom

Given the size of Computer Science’s undergraduate program today — 67% of current Duke undergraduates take at least one computer science class — it’s ironic that the department’s founding member didn’t want it to exist.

“I lobbied against the undergraduate program,” said Starmer. “I lost the fight.”

In Starmer’s defense, even the most fervent proponents of the nascent Computer Science department couldn’t imagine the role of computing in 2023: the proposal for the creation of Duke’s Program in Computer Science estimated that by 1990 up to a million computers could be in use in the United States. In reality, by 2016 that number was closer to 3.5 million in North Carolina alone.

Computers were scarce in 1973, and so were the people trained to use them. People able to effectively teach computer science? Even rarer.

“Another guy and I both taught Introductory Computer Science,” said Bob Warren, the first student to obtain a graduate degree from Duke Computer Science. “I had never taught anything in my life. But it was a lot of fun.”

The problem lasted into the early ‘90s.

“When I started, the people teaching the intro courses weren't actually in the department. They were all local adjuncts from the Research Triangle Park,” said Owen Astrachan, professor of the practice of computer science, who obtained his Ph.D. from the department in 1992.

“I had been a high school teacher, so I came in being a teaching assistant right away, and I talked my way in saying, ‘Hey, you know, I could do this better than them. Please let me,’ and the department did. I was in the right place at the right time.”

The explosive growth in interest in the department’s undergraduate offerings made recruiting more and better teachers indispensable. Duke offered 17 courses in computer science in 1971. There will be over 40 courses offered in the Spring 2024 semester alone. In the past 20 years, the biggest intro classes also grew ten-fold, going from 30 students to 300.

In addition to new topics, Agarwal points out that existing subjects have expanded too. Take algorithms: They were part of the curriculum in the ‘70s, but they didn’t play the societal decision-making role they do in today’s society.

“It's not just teaching the science, but connecting it to technology and to its impact on society,” Agarwal said. “The design of algorithms has become a much richer course because you have to talk about ethics of algorithms. You have to talk about algorithmic fairness. It is important that we teach that in the class — make students aware of it.”

“Computational thinking is now a lens through which you can see the world differently. So the focus is no longer on programming; it’s about problem solving at a scale,” he added. “That has really changed how we teach computer science, because the students who are interested in in it have changed a lot, and we have to adapt.”

Being embedded in the Trinity College of Arts & Sciences, the heart of Duke’s liberal arts educational model, allows students to pour into computer sciences from a variety of extremely different disciplines. This isn’t just a coincidence. It was part of the major’s design.

“Some students seem to be bitten by the ‘computer bug,’” wrote Ramm, who was the Director of Undergraduate Studies in 1972, in a proposed set of requirements for the major. “These students seem to lose interest in everything else. This program attempts to ensure that students develop an alternate area of expertise.”

“Some of the most fruitful areas for research and computer applications lie waiting to be discovered in areas where computer science overlaps with other fields,” he continued.

Five decades later, this is still true: “We are very, very lucky to be in Trinity,” said Pei, “because it really immediately connects us with the humanities, with arts, with social science, with other quantitative sciences like math and statistics. And this gives us a huge advantage to make Computer Science really a human-based, human-enabled discipline.”

Computer Science students and alumni prove the point.

“Because Duke was able to give me such a well-rounded computer science background, I've been able to take leadership positions and conversations that span a variety of different areas,” said Amy Hutchins, T’05.

“It's funny, I took a class on religions in Asia. And that has given me the ability to have a conversation in a way that I don't see other people having them. I probably relate back to that class more than I would have ever imagined when I took it.”

“I came in thinking of majoring in chemistry,” said Yura Heo, a current sophomore majoring in Computer Science. “And then I took CS 101 completely randomly, and just fell in love with the language and with the things I could do with the tools that I learned there.”

Pursuing Greater Diversity

The department’s exponential growth in enrollment and the upswell in classroom size brings with it a wider breadth of student backgrounds and prior experience. But amid this positive development, other challenges come to the forefront.

“In the mid ’90s to the mid 2000s, you probably couldn't major in computer science without having me for a course,” said Astrachan. “I knew almost everybody that I had had in class. It's different now. I just don't get to know people in the same way.”

“I especially think about the students who have been historically marginalized in computing,” said Nicki Washington, Cue Family Professor of the Practice of Computer Science. “I think it is very easy for them to fall into even more invisibility here because faculty likely will not know who they are. It's harder to want to speak up in a class of 300 when you're one of the few who look like you or you don't feel like you have the same preparatory privilege that other students had.”

“Quite frankly, I think we're still struggling with it,” said Professor of Computer Science Kamesh Munagala. “We don't have the kind of resources we need to split a class such as CS 101 or 201 into three or four sections. The courses we teach are very well liked, but the reality is that everyone wants to do CS, so it's challenging for us to give everyone a great experience with the kind of resources we have.”

“Diversity is very, very important for computer science and for technology,” said Pei. “It is not just because we want diversity. It’s because diversity creates new areas, new directions, new inspiring incentives and better connections with society.”

“Duke is a major word in the sentence of me committing my life to bringing diversity to the tech space,” said Meka Egwuekwe, co-founder and executive director of CodeCrew. “Unfortunately, when I was here in the ‘90s, diversity, from the context of those under most underrepresented in tech, was sorely lacking.”

He mentions his experience as the motivation behind his current work opening the doors of tech to children and adults from backgrounds traditionally underrepresented in the field. “If we are going to remain competitive as a nation, we've got to dig deep into that bench to bring those groups into the space.”

Egwuekwe isn’t the only one using his identity and experience in computer science to create change.

Washington is addressing the discipline’s and the department’s lack of diversity head on. As the director of the Alliance for Identity Inclusive Computing Education (AiiCE), a nationally funded partnership aimed at reducing systemic barriers to Computer Science, she leads a postdoctoral fellowship program that prepares junior computer science scholars interested in increasing access and retention of underrepresented students in computer science. She also leads the Cultural Competence in Computing (3C) Fellows program for computer science faculty interested in creating more equitable and inclusive courses and departments.

At Duke, her flagship course, Race, Gender, Class and Computing, introduces students to perspectives different than their own, providing them with the sociological context to explore the impact of computer science on people with different identities.

“Computer science faculty are not taught about topics like race and ethnicity and disability and sexuality,” she said. “So the creation of that course, as well as the creation of the 3C Fellows program, were rooted in my experiences as a Black woman in computer science, on faculty where I am typically the only person who looks like me.”

Duke Computer Science has made progress in one particular axis of diversity: gender. Only a quarter of the department’s faculty members are women, as are a quarter of the graduate students, but in the past 15 years the proportion of women obtaining an undergraduate degree from Duke Computer Science went from less than 10% to closer to 40%.

DTech, or Duke Technology Scholars, has played an essential role. Since its founding in 2016, 1,075 women have taken part in the program, which aims at improving graduation rates for female computer science majors and helping them obtain internships in the industry. The students gain a rich community of peers, mentors and potential professional contacts.

“You don't need experience at all,” said Heo, the current sophomore. “I wasn't even declared as a CS major when I joined DTech, and I got to learn so much up from it because the community is just amazing.”

“We’re at 30 to 35% female in our major and we’re ahead of our peer schools in that way,” said Astrachan. “But we would like to be able to be representative of Duke’s overall population, so we have some work to do. Many people in our department are working intentionally in that direction, trying to make our courses, especially our first few courses, much more cooperative and collaborative in nature and emphasizing working together towards the common good.”

The next 50 years

Astrachan chuckles when asked about the next 50 years of computer science: “What's it going to be? Implants? Are we going to be cyborgs?”

In a more serious tone, he continues: “We still don't really know what's going to change in terms of the technology, but I'd like to look 10 years out and hope that we will be inviting the whole spectrum of Duke students to take Computer Science.”

He isn’t alone in wishing for a future with broader access to the discipline.

“We are a top research department, and we want to be at the cutting edge of technological change,” said Munagala. “At the same time, we want to be mindful that we are taking everyone along. Whenever there has been massive technological change in the world, it has often been accompanied with social unrest and revolutions. That is because people get left behind and these people get rightfully angry.

“We can't fix all the world's problems, but we have to at least make sure that we are giving everyone equitable access to CS education,” he said.

Washington hopes to see a collective commitment to increase access and retention of underrepresented minorities in Computer Science. “As with any movement, it can’t just be the people who are the most disadvantaged that are pushing. Those people are usually the smallest in number, and the most vulnerable to any repercussions.”

She sees good signs of progress in the discipline as a whole, in the form of faculty hires, publications and conference sections focused on the intersection of equity, social justice and computer science. “I think that speaks volumes and is a testament to how the greater CS community is getting on board with the idea that computing does not exist in isolation of the world and that it is influenced by and also influences society.”

“Duke Computer Science is definitely advancing ourselves to embrace those new opportunities,” said Pei. “We are not just staying on the last 50 years of history. We are creating the new history.”