Anywhere you stand on West Campus you’re surrounded by what novelist Aldous Huxley called “the most successful essay in neo-Gothic that I know.” Gargoyles and grotesques, broad lawns surrounded by stone walls, bells ringing as the sun sets. And OK, calling the look medieval may be a stretch, but Duke definitely feels a bit like a place

out of time.

And it’s more than just looks. Poke around and you find craftspeople plying trades every bit as old as the look of Duke’s stone quads: binding books, cracking stones, conserving paintings, managing temperamental organ pipes. The Duke University Libraries, Duke Gardens, the Nasher Museum of Art, and Duke Chapel all need the kind of attention that only the most traditional crafts supply.

Stone

LAID BY HAND

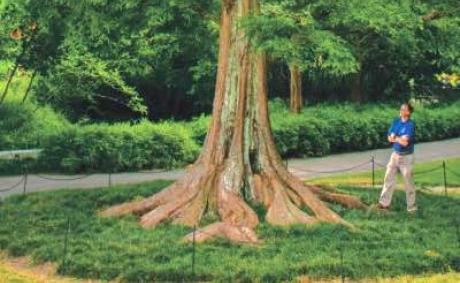

Brooks Burleson makes the dry-laid stone walls that you see all over Duke Gardens. They’re beautiful, relying on a craft as old as humans laying stone, but that’s not why he does it. “Retaining walls have function,” he says. “Dry stone walls do well because they allow water to pass between the stones.” If you use mortar you need a ton of drainage, which is more work and more expensive. Speaking of drainage, you’ve stepped across Burleson’s work a thousand times as you’ve walked through the gardens. Almost all those stone swales – the little drainages that run in angles across pathways – are Burleson’s work.

He does decorative work as well. The Story Circle incorporates old millstones from China, patterned into a mosaic of flagstones. “I designed this,” he says. “What I want it to represent is information flowing out to the kids.”

And beyond stone, information is Burleson’s stock in trade. He’s been through many training programs for his stonework and is now a member of the Stone Foundation, a national organization for sharing principles and techniques, though these “used to be handed on from master to apprentice,” he says. He has mentored many, and he shows off his skill by trying to jiggle a stone just beneath the top row, or coping, of a wall. “You see?” he says. “It’s a small stone, but I can’t pull it out, because it has to extend into the wall.”

Apart from the almost numberless steps and pathways in the gardens he’s proud of things like the woodland stone bridge, which arches over a little creek without, of course, any mortar. But perhaps most important to him is his ethos, like stonemasons before him, of trying not to waste material, and to use local material whenever possible. Some of his mosaics in the Gardens include elements like old slate shingles and roofing tiles. “I want to have some responsibility for not wasting,” he says. “Reusing. Reclaiming.”

Organ Pipe

MAINTENANCE

Up a few spiral stairs, John Santoianni, the Ethel Sieck Carrabina curator of organs and harpsichords, steps into a room barely big enough for two. He swings wide wooden panels and there, suddenly, are a few thousand organ pipes. No exaggeration: The Benjamin N. Duke Memorial Organ, the one in the arch separating the narthex and the nave of Duke Chapel, has 5,033 speaking pipes. They have upper and lower lips, bodies, feet and toes, according to Santoianni. Although that’s only the flue pipes, which make their music like a recorder: blowing wind across the “mouth.” Wooden panels move as wind gates control the air, pulled by cords through wooden pulleys. Wooden ducts guide the air, although air is now moved by blowers, no longer by “sweaty people back there pumping.”

Reed pipes, he says, have a brass “tongue,” just like a clarinet reed, that the wind causes to vibrate. He shows off the tools he uses to tune: a tuning cone, which flares the trumpet of a pipe to make it sharper or tamps to make it flatter, and a tuning iron, which allows him to tap the tongue to change its resonance. He carries a narrow wooden toolbox he made to fit the perches where he clambers among the pipes.

A large part of tuning comes in response to weather. The sun shines, the air heats up, and a perfect A goes a couple hertz high and needs attention. Giant pipes, like the ones you see at the back of the chapel, respond at one rate; ones the size of a soda straw respond at another.

“As long as we have weather,” he says, “I’ll have work.” The combination of his musical taste and family tradition guided him. “My father’s father was a machinist,” Santoianni says. “My father was a mechanical engineer. My brother is a mechanical engineer.” He sighs.

“You can run, but you cannot hide.”

Book

CONSERVATION

Beth Doyle, Leona B. Carpenter Senior Conservator and head of conservation services at Duke libraries, shows off a porcupine quill she received from a mentor. “You can poke things with it,” she says, a sly way of saying book conservation requires any number of tools for pressing, folding, and manipulating books. She says that, apart from the standard tools provided by the lab, each conservator will have their own set. Like her quill, or “the nicest bone folder you’ll ever find in your life,” made from elk antler and perfect for creating a sharp crease.

“One of the things I love about conservation is it marries the old world craft with modern science,” she says. That is, she’ll have that porcupine quill and other tools that haven’t changed in centuries, but she’ll also rely on modern solvents and glues. Like senior conservation technician Jovana Ivezic, working quickly through a tub of fast-drying adhesive she made to “reback” books that need their spines replaced. She uses buckram, though the supply room has many varieties of cloth to connect the boards of the covers with the spine. She weights them with boards with brass edges to press down a crisp joint, which allows for easy cover opening. Need more weight? “Large Marge” is their gigantic book press, with a screw mechanism little changed from those you see in medieval illustrations.

Or watch Henry Hebert, conservator for special collections, at work on a book of William Hogarth etchings, shown above. “We sometimes take a book apart and wash it,” he says, patiently unbinding and unsewing a book, giving it a special bath of treated water to remove dirt without affecting the ink of text or artwork, then reassembling it.

Art

CONSERVATION

How long have people been caring for artwork? “Since artists have been making art,” says Ruth Cox, who conserves artworks for the Nasher Museum of Art and other museums all over the world. “They probably took care of cave paintings” tens of thousands of years ago at the dawn of human art.

She speaks showered by the “true north light” in her Durham studio, about the size of a garage with 12-foot ceilings. “Look at Rubens,” she says. “His paintings for Philip IV of Spain were damaged in shipping, so he conserved them when they arrived.”

“My specialty is old masters,” she notes, such as a piece she is currently working on for the Nasher. “Architectural Capriccio With Figures,” painted around 1717 by Giovanni Paolo Panini, requires her to use tiny dabs of acrylic paint to fill spots that have come with years of storage. On another work, she demonstrates how she resettles peeling paint with a heat gun, a tiny silicone spatula, and almost limitless patience. Beforehand she had put adhesive into the cracks with a tiny brush. On a nearby three-level cart sit dozens of jars: solutions, gels, emulsions, each with a specific purpose. “They differ in pH, they differ in viscosity.” She uses watercolor and acrylic paints, transmitted and ultraviolet light, microscopes, adjustable LEDs and chemicals beyond imagination.

of Henry Ward Beecher by Francis B. Carpenter, before treatment.

of Henry Ward Beecher by Francis B. Carpenter, after treatment.

“More important than the material that we’re using,” she says, “is the eye and the thought and the hand.” The job of the conservator is to understand what the artist had in mind and bring the object as close to that as possible. There are now graduate-level programs in conservation, but the skills haven’t changed much since they were passed down, master to apprentice.

“It’s really fun to unravel the stories of all these pictures,” she says. “That’s what I do with pictures: You want the picture to be able to tell its own story again.”