In 1925, Duke was still just a baby. With a new name and an expanding campus, there was a desire to introduce new traditions that distinguished it from any other school. There was also a desire to integrate freshmen into the Duke community – and ideally, these new traditions would not take the form of hazing, which had been a problem in the earlier years of the school.

Back in 1906 sophomores pledged not to haze freshmen, but it appears that the problem persisted. In 1924, white badges with blue “F's” were distributed to male freshmen. The Chronicle student newspaper reported that “…there is every reason to believe that if it is carried out in the right way that it will practically eliminate the annual hazing parties.” The details of such parties are rather scant in the student press, but a 1928 letter to the editor in The Chronicle bemoaned the loss of “the customary ducking and bed lifting agonies.” (Your guess is as good as mine.)

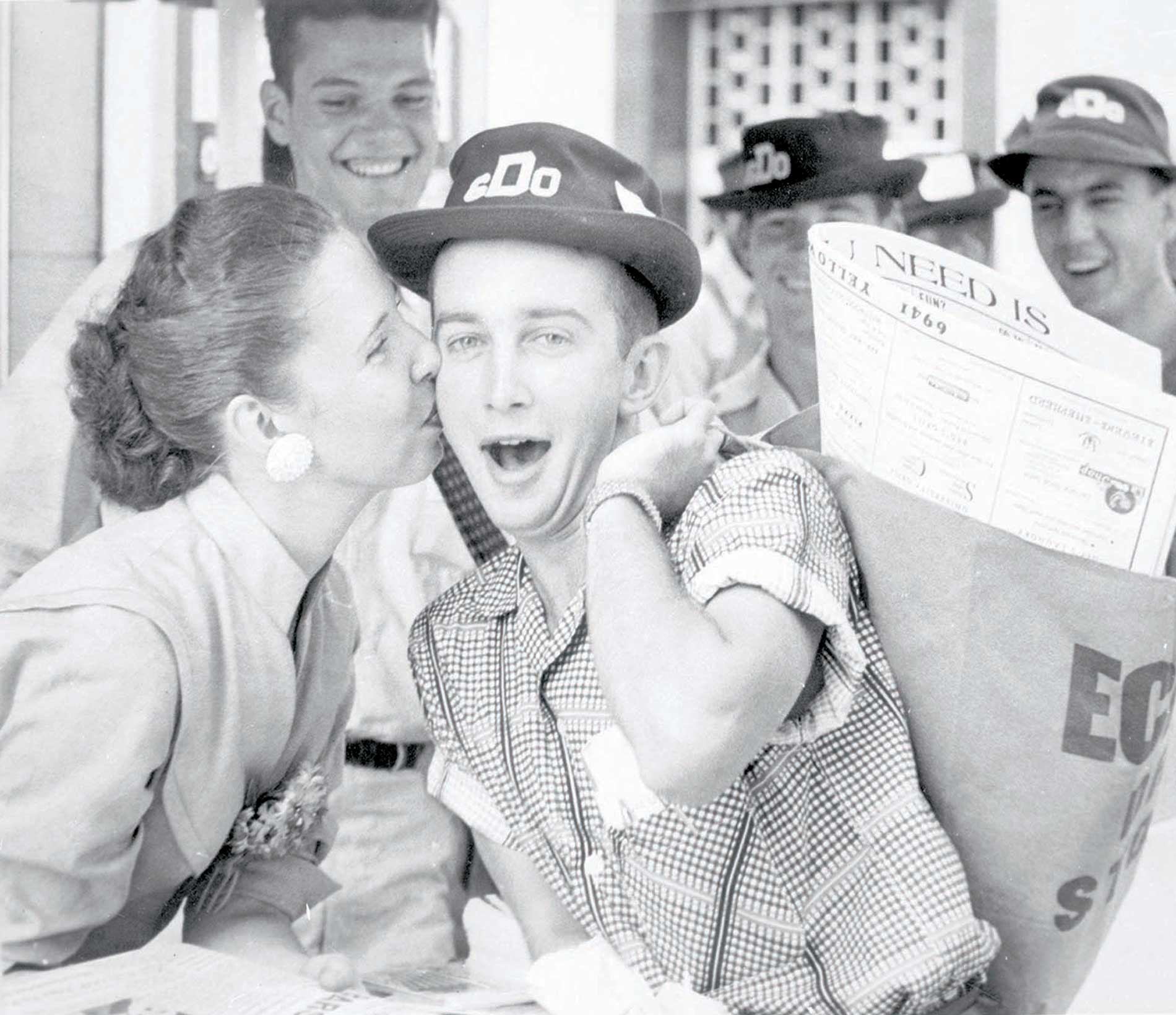

In 1925, based on the success of badges, the more “stringent” practice of blue freshman caps was established. An article in The Chronicle on Nov. 25, 1925, declared “Freshman Caps Are Successes Say Sophomore.” A sub headline intriguingly continues “Prophesies of Evils Are Not Being Fulfilled – Class Spirit Among the New Men Has Been Improved.” The school spirit shown among the freshmen made the caps a regular feature of freshman life at Duke. They also easily demarcated freshman students, from whom the sophomores could demand a recitation of “Dear Old Duke” and a hat tip, and be quizzed on Duke history trivia.

The caps were originally intended to be worn throughout the school year, but in February 1926 it was announced that “the conduct of the freshman class has been so satisfactory that the freshman caps may now be abolished for the remainder of the year.” Being Duke students through and through, the freshmen built a bonfire and burned their caps, soon to be colloquially known around campus as “dinks.” They were later restricted to the first semester only, although if Duke beat UNC in their annual football game, the freshmen could remove them at that point – making the football game a marquee event of the fall. In 1941, smarting after a painful loss the previous fall, the Men’s Student Government Association (MSGA) passed a motion that dinks could be removed on Dec. 1 “in case we ever again lose to Carolina.”

While the dinks were silly, there were consequences for men who didn’t comply. First the MSGA, and later a specially designated committee, would identify men who didn’t wear the hats, call them before the review committee, require them to wear yellow dinks, with consequences for continued non-compliance ranging up to expulsion (no dink-related expulsions have yet been discovered). Infrequently, students could request special permission to not wear the dinks. The minutes of the MSGA in November 1932 report that “William L. Holler, Columbia, South Carolina, appeared before the council, asking that he be permitted to discontinue wearing his freshman cap, in as much as he was 25 years old upon entering Duke, and that he had been out of school for five years at work, feeling very much out of place in wearing the cap. After a discussion, it was decided to grant Mr. Holler the concession.”

The women of Duke University adopted a practice similar to the men’s beginning in the 1930s, except they used hair bows, not dinks, to demarcate the first-year and upper-level students. The hair bows were printed with the class year, and non-compliant students were given red hair bows. The ritual culminated in the event known as Goon Day, where freshmen women were paraded around campus dressed like babies in bibs and pajamas, forced to simultaneously wear ankle socks and high heels (a faux pas), or required to tote around a placard announcing their goon status.

The years of World War II disrupted these traditions, but they were resumed in 1945, when an October Dink-Bow Day was held, described in The Chronicle as “a combination games and listening party” with a king and queen “chosen by the sophomore class presidents on the basis of the cleverest outfits.” The freshman women were asked to wear their clothes inside out and backwards. While the tradition was back, the rules became more relaxed. Those who didn’t wear their dinks were made to pass a test on Duke history and, if necessary, be assigned “some duty such as cleaning statues, painting chain posts and other constructive activities that also might be enjoyed when done in a group.” In 1955, the MSGA made the dink-wearing period only six weeks at the longest, and in 1957, cheeky freshman women in Jarvis Dormitory “dyed their bows lavender, and still other individuals have sequins and polka dots on theirs.”

In fall 1960 The Chronicle published an editorial suggesting the days of dinks were in the past: “The wearing of dinks, we think, does little to foster class unity or love for the University. Most freshmen want simply to get rid of the obnoxious hats which mark them as inferior citizens.” In 1961, the MSGA ceased the dink tradition. Women students held on to the bows a bit longer. In a 1963 article about the tradition, it was reported that “Fledging East Beasts were harassed and humiliated by the ‘powers above’ – the sophomores – during initiation into the noble traditions of the Woman’s College. Freshmen were forced to chant their inferiority, submit to having flour and shaving cream rubbed into their beautiful tresses, and wear white bows and name tags in unusual locations on their person.” Wearing bows (and its attendant humiliations) finally ceased in 1968. Duke’s student body today is made up of people from around the world, and we celebrate having classes of students that come from a wide variety of backgrounds. The love of Duke remains, but the role of sophomores in “teaching” freshmen through pop quizzes and backwards clothes is non-existent. Freshman traditions today include taking a class photo in the shape of the numbers of their graduation year and enjoying experiential, thematic orientations. We don’t need hats or bows to be initiated into the Duke community – if you’re here, you belong.